Among the most famous Ukrainian films of the first half of the twentieth century, Oleksandr Dovzhenko's "Arsenal" holds a special place. Innovative from an artistic point of view, the film was dedicated to one of the most significant episodes of the Ukrainian Revolution of 1917-1921. On the centenary of these events, it is worth taking a closer look to see if anything of what the master wanted to say with his work has gone unnoticed.

In addition to its artistic value, the film stands out among other historical films of the time because the director was a direct participant in the storming of the Arsenal factory. At the same time, although the events in the film are covered from the point of view of the Bolsheviks, Dovzhenko was on the other side, as part of the Ukrainian army.

Soviet cinema of that period did not aim to accurately reflect historical events, but rather to construct a certain myth, the features of which were laid down by the propaganda concept in force at the time. Before "Arsenal", Soviet films about the events of 1917-1921 were mostly dominated by adventure stories. This made it possible to show the events in a rather fragmented way, without giving a general picture that would have to be reconciled on many levels. In "Arsenal", we see not just a historical plot, but a holistic concept of the struggle between "Soviet good" and "Ukrainian bourgeois nationalist evil."

Thus, Dovzhenko's film is not just a feature film, it is a kind of manifesto of the Soviet government's attitude to the Ukrainian struggle for independence, and as such, it contains all the necessary accents in the plot, in the characters, in the images. Nevertheless, the authorities accused Dovzhenko of nationalism, based on his undisguised sympathy for everything Ukrainian, as well as the director's active use of metaphors and symbols that could have a double meaning.

When “Arsenal” was released, many participants in these events were still living in the USSR, including those who fought on the side of the UNR. In particular, Omelian Volokh, who stormed the Arsenal at the head of the Haidamak Kosh; later he staged an unsuccessful “leftist” rebellion and fled to the Bolsheviks. According to the sister of Dovzhenko's first wife, Varvara Krylova, the future director belonged to the Black Haidamak battalion, a part of the Haidamak Kosh, and was under Volokh's command. Given the small size of the battalion (up to 150 bayonets), they must have known each other personally.

Among the signs and symbols used by Dovzhenko in “Arsenal” were things that were obvious to people whose consciousness was formed before 1917, and perhaps not so obvious to the younger generation. And there may well have been signs encoded that were understandable primarily to those who fought with him in the ranks of the Ukrainian army.

Unfortunately, researchers usually analyze the artistic context of “Arsenal” while ignoring the historical context of Dovzhenko's symbols. The author of the article cannot guarantee a one hundred percent correct reading of these elements of “Arsenal,” but this attempt may be interesting for understanding the director's worldview.

Despite the above-mentioned concept of the struggle between good and evil, the plot of the film is not coherent and effectively connected; its connection is rather imaginative. It often jumps around in time and space (for example, at the Ukrainian Congress, Petliura is announced as the Chief Ataman, which he will become a year later). Gradually, logical paradoxes accumulate to explode at the end of the film, leading to the scene of the protagonist's execution. This greatly adds to the epic nature of the film, which, in turn, avoids consistent coverage of historical events where Russia would look like an aggressor. The suffering of the people during the First World War at the beginning of the film forms the overall canvas. The appearance of the Tsar creates a familiar discourse of confrontation between the classes of society. The Arsenal itself appears in the film towards the end, and the first 50 minutes are devoted to the formation of Timosh's (protagonist) character. By all appearances and behaviors, he is a typical Bolshevik, as presented by the propaganda of the time. He appears on the screen after the tsar, which emphasizes his position in the discourse. At the same time, we can understand that he is not a member of the party and is a Ukrainian by birth. Thus, we have a typical hero who is easily “read” by the audience of that time. The very epic nature of the work requires that we focus on the hero's personality and his “local” adventures. Accordingly, his conflict with another organized force, the Ukrainians, is interpreted as the main conflict of the decade from the Bolshevik point of view: Reds versus Whites.

To present the openly left-wing Ukrainian government of late 1917 as a kind of Russian right-wing, white movement, the director devotes a lot of screen time to the events on St. Sophia Square, the streets of Kyiv, and shows the Ukrainian Congress. At the same time, he emphasizes people of a “non-proletarian” type. Costumers and makeup artists reinforce this effect, which is also emphasized by the camerawork. Finally, by showing events that are close to real, the director shifts the emphasis, presenting the Ukrainian movement as exclusively “bourgeois” and rather awkward. Hundreds of original photographs from that time show that this was not true. In general, these characters quite clearly correspond to the pre-revolutionary image of the “mazepynets,” which was often described in the Russian periodicals, in particular the newspaper “Kievlyanin”, and thus were familiar to the audience whose mentality was formed before 1917.

Ukrainian demonstration in "Arsenal"

Ukrainian demonstration in "Arsenal"

Ukrainian demonstration in "Arsenal"

Ukrainian demonstration in "Arsenal"

A real Ukrainian demonstration, 1917

When Dovzhenko shows a congress, logically, it must be the All-Ukrainian Congress of Councils of December 4 (17), 1917 - December 6 (19). However, given the rather free use of time in the film, it is quite possible that this is not a specific Ukrainian congress, but a generalized picture of such events. At least, the credits at the beginning of the congress only say that it was the “first all-Ukrainian” congress, so it could be the All-Ukrainian Congress of Councils, the All-Ukrainian National Congress, or the First All-Ukrainian Peasant Congress.

Here we encounter the first interesting paradox that allows for a double interpretation. Dovzhenko shows a message with threats from the Ukrainian Black Sea Fleet to the Central Rada. It is difficult to understand whether this episode has any historical basis, because we know from documents and memoirs of participants in various Ukrainian congresses that Ukrainian sailors usually sent congratulatory messages to the Central Rada. Moreover, in the late fall of 1917, Kyiv hosted a marine battalion named after Hetman Sahaidachnyi, sent from Sevastopol to defend the Ukrainian government.

The need for an episode showing the hostility of Ukrainian sailors to their own political leadership was obvious to the Soviet authorities. But the form in which Dovzhenko accomplished this task makes us wonder whether he did not want to deny the content of the episode with this form. The message from the sailors is followed by a symbolic “vote” signed with the names of two ships: the dreadnought “Maria” and the “Three Saints.” Naval topics were widely covered in the media of tsarist Russia, so these names carry a certain connotation. For the Black Sea Fleet, the tsarist government built four dreadnought battleships: “ Empress Maria,” “Empress Catherine the Great,” “Emperor Alexander the Third,” and “Emperor Nicholas the First.” The first three were completed by 1917. “Empress Maria“ sank in Sevastopol harbor on October 7, 1916, from an internal explosion under unclear circumstances. Among the versions were: carelessness in handling ammunition, German sabotage, socialist sabotage, etc. “Empress Catherine the Great” became “Free Russia” after the overthrow of the tsar, with the Russian revolutionary parties having a serious influence on the crew, and “The Emperor Alexander the Third,” the newest of the three, was renamed “Volya” ("Freedom" in Ukrainian, more about this ship read in "Volya" in Trebizond" here: https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0CX9GY3M2) by its Ukrainian crew. In the twentieth of December 1917, it was Ukrainianized, and as the most powerful ship under the Ukrainian flag, it was a serious irritant for the Bolsheviks.

Thus, the appeal to the Central Rada had to be signed by the largest force in the Black Sea Fleet, either “Volya” or “Free Russia.” The signature of “Free Russia” would have disavowed the essence of the Ukrainian sailors' appeal to their political leadership, so it had to be “Volya.” If the congress we see in the film is the All-Ukrainian Congress of Councils, then at the time of its holding the dreadnought Volya was still flying the Ukrainian flag. Perhaps Dovzhenko, who in December 1917 followed the epic of the seizure of the Black Sea Fleet ships by the Bolsheviks through newspapers (by the way, similar to the events of the spring of 2014), did not dare to go against historical facts? Perhaps he was afraid of the party's wrath by mentioning the ship that had the largest Ukrainian community in the Black Sea Fleet, on which the Ukrainian flag appeared in the summer of 1917, and which was captured only in January 1918 after threats and a blockade?

So Dovzhenko wrote: "Maria" is a ship that perished a year ago, a phantom force that was associated in the imagination of an adult viewer with sabotage.

The next signature is “Three Saints”. Except for the dreadnoughts, the strongest ships in the Black Sea Fleet were two pre-dreadnought battleships of the same type, the “Evstafiy” and “John Chrysostom.” Although they had been built just before the First World War, the very idea of an pre-dreadnought battleship had become obsolete after the advent of dreadnoughts, and they could only be used against a weaker enemy. These two ships were built on the basis of the design of the “Prince Potemkin Tavrichesky”, which, in turn, was based on the design of the “Three Saints”. The ship was laid down in 1891, and despite its modernization in 1912 and active participation in hostilities against Turkey, it was hopelessly outdated.

So, instead of three battleships that still had some combat value, the appeal is signed by an obsolete and physically deteriorated ship.

More about the situation on The Black Sea Fleet is here

Were these inscriptions really a manifestation of Dovzhenko's opposition to the Soviet system, or were they prepared by another person who was unaware of the realities of 1914-1917? Perhaps this question requires further research.

After a long backstory, we finally see the workers and the Arsenal plant. This story is presented without specific events, in an imaginative way. On the one hand, this gave Dovzhenko ample opportunity to use the latest dramatic editing and camerawork techniques, and on the other hand, it freed him from comments about the correspondence or inconsistency with real events. In addition, though Dovzhenko hardly thought about it, it made the film more resistant to changes in Soviet versions of the revolutionary history-a problem he would face in his later film “Shchors.”

Images of the battles around the Arsenal alternate with footage of the invasion by Muravyov's Russian army. A certain illogicality of editing joints, the paradoxical mention of “the year of civil war (which was just beginning in those days, according to Soviet historiography) after four years of world war”, the display of Russian horsemen against the backdrop of Ukrainian houses - all these filmmaking techniques allow to distract the viewer's attention from the fact of the Ukrainian-Russian war, to create the illusion of the Ukrainianness of the Russian army.

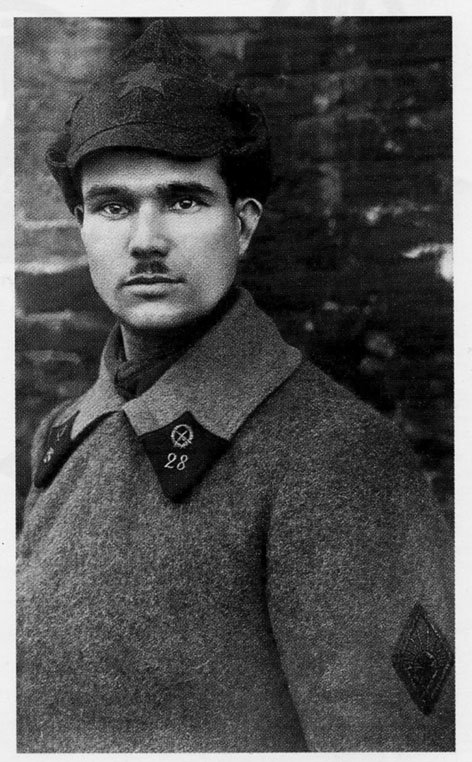

In the last part of the film, we can note the extensive use of typecasting, manipulation of uniforms and symbols to form the images Dovzhenko needed. The protagonist is constantly dressed as a soldier of the Russian army, but without insignia. The former soldier, while not representing a specific political force, represents the people. Some of his accomplices in the Arsenal and the Russian interventionists are dressed in the same way. This partially corresponds to historical realities, although Muravyov's army is shown as too monotonous, homogeneous, and proletarian: there are no Russian officers on the screen, who were quite numerous. This technique allows us to unify everyone fighting on the protagonist's side.

The episode with the “Free Ukraine” armored car is interesting in terms of uniforms. Most likely, the episode was based on the actions of the First Ukrainian Armored Car Division, described in the memoirs of Stepan Samiilenko and others. All ten Ukrainian panzer divisions had names, but Free Ukraine was not among them. Perhaps the name was chosen for the sake of symbolism in the phrase from the credits “Did you overturn our ‘Free Ukraine’?” This episode shows a Ukrainian soldier wearing something that looks like a jacket, but with a white collar and something resembling a tie. We have already seen a similar character at the congress: this is the image of a Ukrainian intellectual, a non-military person, while the personnel of the armored car division consisted of front-line soldiers, and they were dressed accordingly, in Russian-style uniforms and leather jackets. His manner of holding a revolver was also not frontline, but rather “bookish.”

Ukrainian soldier from an armored vehicle

A man who looked like him at the Congress

The crew of a Russian army armored car

In the following episodes, among other Ukrainian units, judging by the uniforms, we can primarily identify the Haidamak Kosh (coats and striped hats) and the Kyiv Free Cossacks (a mixture of military and civilian or mostly civilian clothing).

More about the Free Cossacks of Kyiv in restored newsreel here.

Dovzhenko shows volunteers dressed in civilian clothes and almost avoids showing Ukrainian regular units on screen. Occasionally, two-colored caps (most likely yellow and blue, i.e., of the Bohdan Khmelnytsky regiment) appear for a moment, and only for a moment, near the end of the film, can the silhouettes of Hordienko regiment soldiers be seen, (Russian uniforms with no insignia and shaggy Manchurian papahs), but they are shown in cavalry formation, which is unrealistic during the storming of the Arsenal.

Two-color cap

Silhouettes of horsemen, similar to Hordienko regiment

More about uniforms of Ukrainian troops here

At this time, the Russians from Muravyov's army, who once served with the Hordienko men in the 3rd Siberian Corps, appear on the screen frequently. The Sich Riflemen (Russian uniforms with newly designed caps), who fought from the beginning to the end of the war, are not in the picture at all.

Given that the regular army is considered one of the main attributes of statehood, its absence on the screen seems to deny the Ukrainian right to its own state, making Ukrainian attempts at state-building look comical and futile. In general, all Ukrainian formations from the beginning of the film appear undisciplined and prone to violence and looting.

As for the Bohdan Khmelnytsky Regiment, there is also an interesting point. Toward the end of the movie, you can see the soldiers with two-color caps better. However, instead of wearing military overcoats with Ukrainian lapels with the monogram “BKH”, they are wearing black overcoats with Russian buttonholes and buttons. The black overcoats are not military, they are students, officials, not proletarians. The Russian buttonholes instead of the Ukrainian lapels seem to hint that the Bohdan Khmelnytsky Regiment was a kind of Russian White Army (which later also used two-colored caps, but in different colors), and thus enemies of Ukraine and the working people.

Two-color cap, black overcoat, Russian buttonholes

Thus, ordinary Ukrainian peasants are shown as representatives of the enemy ruling classes. In addition, the Red Army insignia, contemporary filming of “Arsenal”, almost exactly repeated the shape of Ukrainian Bohdan Khmelnytsky Regiment.

This is what a Bohdan Khmelnytsky Regiment soldier should have looked like (photo from the Museum of the Ukrainian Revolution)

Soviet insignia, photo from the 20s

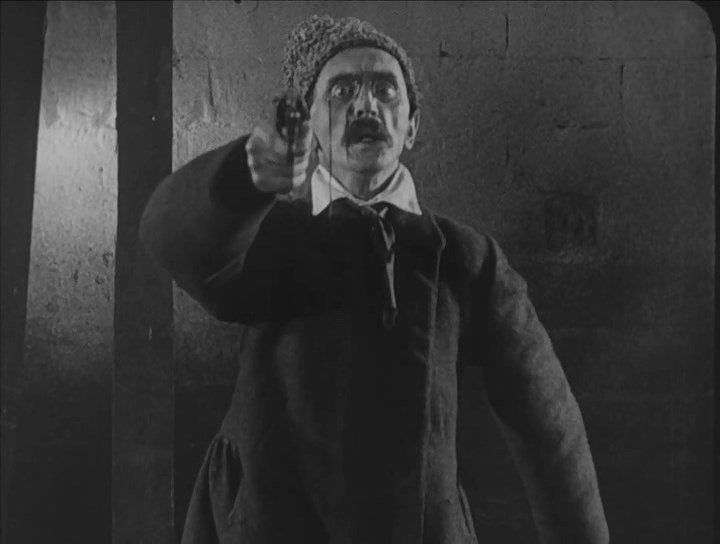

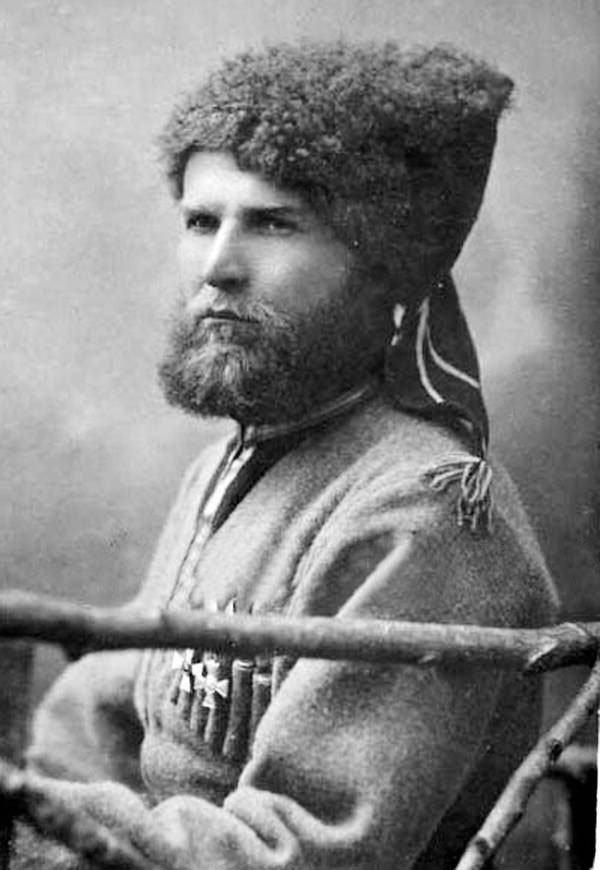

Was Ataman Volokh among those depicted by Dovzhenko? Among those shown in the uniforms of the Haidamak Kosh is a man with a revolver in his hand, who calls on others to attack. We can assume that this is a senior officer. Volokh's famous beard is also in the picture. This is most likely how Dovzhenko portrayed his former commander.

A man functionally similar to Volokh in Dovzhenko's film

Omelian Volokh. Photo from the time of the Liberation War

“Dovzhenko used a ‘free’ interpretation of uniforms not only in ”Arsenal”. The beginning of the film “Shchors” also contains an original scene that can either have a pro-Soviet interpretation or give an openly anti-Soviet color to the entire film.

At the beginning of the film, during the reign of the Hetman, the blue-coated soldiers under the command of Russian officers, together with the Germans, mock the peasants. From the Soviet point of view, everything is correct: the Germans are the occupiers, their puppet, the White Guard Hetman sent Russian officers to help them, and Ukrainian troops serve both.

However, if we take into account that the division of blue-coats was disarmed by the Germans so as not to interfere with Skoropadsky's rise to power, and its former Cossacks later participated in the anti-Hetman movement, the fiction of the scene becomes obvious. In addition, according to many memoirs, the division of the Blue Coats was very patriotic and, moreover, quite socialist. Thus, it is difficult to imagine them fighting against their own people under the command of Russian officers.

Thus, for a person who read magazines in 1918 and was aware of the events, the beginning of Shchors seemed to say that everything that would happen in this movie was not true.

Whether Dovzhenko, while working on Stalin's assignment to create a “Ukrainian Chapaev,” really dared to send such a signal to his “own” people, we will probably never know. However, we can say with certainty that some of the audience of Dovzhenko's films understood them in a completely different way than the Soviet regime needed.

The article was first published in Kino-theater magazine 2018 #1

About the battle that ended the Arsenal mutiny can be read here.

Really interesting, thanks.