The question is complex because cinema was still forming, as was the “star” system, and the concept of Ukrainian identity was (and remains) sometimes problematic. Some readers may have already guessed that we will mention Vera Vasilyevna Kholodnaya, née Levchenko. However, the legendary Poltava native became a symbolic face of Russian silent cinema, and even her last films, shot in Odesa, cannot be considered part of Ukrainian cinematic heritage. Thus, in Kholodnaya’s case, we can only speak of the “star” potential that Ukrainian cinema might have had if it existed as a developed national film industry. (We emphasize: developed, because films were being made in Ukraine and quite actively.)

Another case involving Ukrainian cinema and an unrealized Ukrainian film star is the story of Maria Zankovetska and Mykola Sadovsky in cinema. This concerns already established stars, of not only Ukrainian but also all-imperial scale—just not of cinema, but of theater.

So, 1911, Katerynoslav. The famous troupe of theatrical luminaries is touring the city, including its gem, Maria Zankovetska. At the same time, filmmaker Danylo Sakhnensky, who would later make history with his 1911 film Zaporizhian Sich, lives and works in the same city. Sakhnensky was deeply interested in native history and culture and likely convinced these theater masters to immortalize their performances on film. This practice wasn’t new; in fact, it was what had helped elevate the nascent medium of cinema from a “low” fairground entertainment to... if not full-fledged art, then at least something more respectable. A few years earlier, in 1907, French filmmakers had made serious efforts to expand their audience. To attract a more educated and affluent public, they decided to align cinema with theater—both in repertoire and by involving famous theatrical actors. This gave rise to the phenomenon of so-called “artistic films” (Films d’Art). In 1908, The Assassination of the Duke of Guise, directed by André Calmettes, was released, featuring renowned actors such as Henri Lavedan from the French Academy and Le Bargy of the Comédie-Française. Gradually, other stage stars, including the legendary Sarah Bernhardt, stopped shunning the screen. Interestingly, though, Bernhardt never became a screen star: her age (mercilessly revealed by the camera) and acting style prevented it. The fact that theatrical success didn’t guarantee cinematic success became evident early on.

In the Russian Empire, this idea was quickly adopted. Due to the popularity of Ukrainian theater troupes, Russian filmmakers eagerly filmed them. For instance, Abram (later Alexander) Drankov, known for his entrepreneurial spirit, filmed actors from O. Suslov’s touring troupe in St. Petersburg for movies like Zaporozhets Beyond the Danube, Senatorial Inspection, and Bohdan Khmelnytsky. In 1910, the S.A. Frenkel Joint-Stock Company in Kyiv filmed actors from Mykola Sadovsky’s theater in the vaudeville Three Loves in Sacks, based on Gogol’s work.

Thus, it’s entirely plausible that even the esteemed luminaries could “lower” themselves to the then-lowly art of the big screen. They chose to adapt The Hireling by Ivan Karpenko-Kary and Natalka Poltavka by Ivan Kotliarevsky. Sakhnensky handled the technical aspects, while Sadovsky directed and adapted the plays, selecting key scenes to fit the modest runtime while preserving the narrative. He also acted in both films: Tsokulya in The Hireling and the village elder in Natalka Poltavka. Maria Zankovetska starred only in Natalka Poltavka, playing the titular role. Other actors included Ivan Maryanenko (Mykola), Fedir Levytsky (the bailiff), Hanna Borysoglibska (Terpylykha), and Semen Butovsky (Petro). In a letter, I. Maryanenko later recalled the filming: “This could have been in the summer theater of the city garden, as that’s where our theater’s performances were held. Likely, the filming occurred in the morning without an audience, in the garden... I vaguely recall painted decorations set up in the garden near the theater...” Interestingly, he never saw the films himself—they were released in December (back then, everything was shot and shown very quickly!), and the performers didn’t follow the films’ fates and simply missed them.

The filming process was approached seriously, accounting for the specific demands of the camera: subtle makeup in carefully chosen shades—no rouge or painted lips, but more yellow and pink tones, avoiding blue and black whenever possible. Even the photographic nature of cinema was considered: authentic clothing replaced theatrical costumes for greater realism. Reportedly, Sakhnensky even consulted with and borrowed costumes and props from a local museum of local history (a practice he would soon employ for his famous Zaporizhian Sich). Sadovsky also used his theatrical expertise; he was known for his dedication to authenticity and lifelike characters.

As the author of a study on early Ukrainian cinema, B. Lykhachov, who could well have seen both films, would write in the 1920s, they were filmed “in a theatrical manner,” as they were performed on stage; however, this practice was normal for cinema at the time. On the other hand, Natalka Poltavka remained on screens until 1930 and was enjoyed by audiences — a testament to the film’s quality and the acting, particularly the on-screen performances. Unfortunately, those films have not been preserved, so we can only speculate about what kind of film actress Zankovetska might have been. Nevertheless, judging by recollections of the famous actress’s performances, it can be confidently assumed that she had the talent for acting in silent films. For example, her facial expressions: around 1910–1911, performers began to understand that the exaggerated facial expressions and gestures typical of theater needed to be restrained for cinema. Meanwhile, M. Zankovetska’s facial expressions were simultaneously expressive and natural. As Odessa Herald wrote about her: “The facial expressions of Ms. Zankovetska are unparalleled; they are extraordinary […] The smallest emotional nuances are reflected on her face with astonishing speed. Her face knows no stillness on stage, even […] when she is silent; looking at her face, you can hear, understand what she is thinking and experiencing at that moment.” The actress was often praised for her ability to “act with her eyes.” According to renowned theater scholar P. Rulin, this was not merely a technique but one of the key features of Zankovetska’s acting method: her eyes conveyed the subtlest nuances of her heroines’ emotions. At the same time, the actress could act with restraint, subordinating emotions to the artistic means of a finely crafted role. All these traits are crucial for the big screen, especially silent films. Considering Sadowsky’s approach to theater productions, it can be assumed that it extended to his acting as well; at least in The Hired Woman, critics noted the realism of his performance.

By the 1920s, both luminaries of the acting stage would appear in films: Maria Zankovetska in Ostap Bandura (1924) and Mykola Sadowsky in the Czechoslovak Koryatovych (The Magic Ring of the Carpathians) in 1922 and possibly in The Golden Wolf in 1924. After returning to Soviet Ukraine, he starred in The Last Pilot (Wind from the Rapids) in 1929 and, allegedly, in Vanko and the Avenger (though, it seems, there was a mistake, and the role was played by a namesake, Ivan Sadowsky). But that, as they say, is another story...

And yet — what about actors who consistently appeared in films, were popular, and can be, very conditionally and with consideration of the era’s realities, called stars? Perhaps, yes. Moreover, these were stars... of the era’s equivalent of musicals. In 1909–1911, “cine-declamations” and “cine-talking pictures” — early attempts at “talking cinema” — were extremely popular. The concept was simple: filmed visuals were accompanied by live dubbing by actors, sometimes with music and sound effects. These were mainly adaptations of literary works or popular theatrical performances transferred to film (in fact, “cine-talking pictures” were primarily produced by theatrical troupes). Dance and musical numbers were also an important component of such films, which derived from the predominantly musical-dramatic Ukrainian theater. Proto-musical? One could say so.

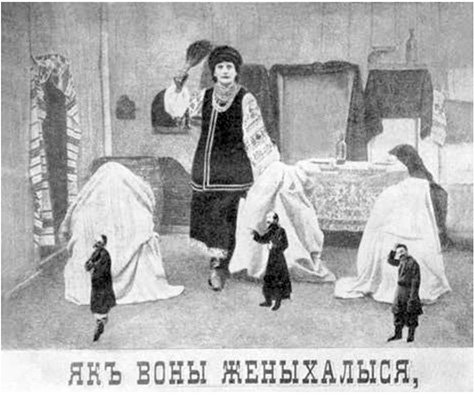

The pioneers and most famous cine-declamators were the Oleksienko couple — Oleksandr and Olena. Oleksienko, the son of a postal clerk, worked as a telegraphist in his youth; however, captivated by theater from childhood, he eventually joined a theatrical troupe led by D. Haidamaka with his wife. The couple quickly gained popularity, particularly for their musical and dance performances. They became especially renowned thanks to the big screen. In 1909, Oleksienko tried his hand at cinema by creating the first Ukrainian cine-declamation — a one-act comedy-vaudeville How They Wooed, or Three Loves in Sacks, based on Gogol’s The Night Before Christmas, in which he played all the roles: the deacon, Chupryna, Holova, and Solokha. In an exaggerated style typical of the time, advertisements proclaimed: “Sensation!!! A new trick in cinematography! A talking picture without any gramophones, titled How They Wooed, a one-act cine-vaudeville with singing and dancing, with voice imitation perfectly synchronized with the characters’ dialogues. Performed solo by the author, transformer O. M. Oleksienko.” The press noted the “complete illusion” achieved by the performer. Perhaps the greatest possible compliment for a film of that era, from the esteemed Sinefono, stated that the cine-picture “... is not one of those infamous ‘attractions,’ but relevant to our field and brings much animation to our silent films.”Inspired by his success, Oleksienko continued to work, but not alone: his films featured his wife Olena, as well as F. Maslov, Maria Kalyna, and Vasyl Vasylenko. These were mostly vaudevilles, specifically Ukrainian ones: The Charmer Moskal by I. Kotliarevsky, The Miller Godfather, or the Devil in a Barrel and Matchmaking at the Evening Party by D. Dmytrenko, If There’s Sausage and a Shot, the Quarrel Will Pass by M. Starytsky, A True Story, or Don’t Covet Another’s Bread by A. Velysovsky, and others. Oleksienko did not pay much attention to the specifics of cinematic art; his vaudevilles had an overtly theatrical origin, from staging to costumes and sets. On the other hand, he actively employed purely cinematic techniques, such as close-ups to better convey the characters’ movements and expressions, ensured the frames were dynamic (as much as was possible at that stage), and began to pay attention to the realism (albeit conditional) of the sets. In any case, the theatricality did not hinder the films’ success with audiences. Perhaps the opposite? Ukrainian vaudeville was well-known and loved, and the audience was accustomed to its artistic language. Cinema was still perceived more as “live photographs” than an independent artistic language.

Despite their success, talking pictures did not bring wealth to the creator — a common situation for cinema pioneers. Films were made and sold quickly, but “talking pictures” were more complicated to produce and were often shown as a supplement to the main program. Yet audiences lined up to see Oleksienko’s films, and he had imitators — Oleksandr Ostroukhov-Arbo, Yakym Karatumanov, and others. Most importantly, he and his actors went down in history as people who brought crowds to Ukrainian cinema. And this, we note, was during a time when everything Ukrainian was considered inferior and closely monitored by censors.

So let us remember our stars! Both those who diligently served the new muse for years and those who illuminated the screen for just a moment...

Literature on the topic:

Zhurov H. From the Past of Cinema in Ukraine. 1896–1917 / H. Zhurov. – Kyiv: Publishing House of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian SSR, 1959.

Shymon O. Pages from the History of Cinema in Ukraine / O. Shymon. – Kyiv: Mystetstvo, 1964.

Myslavskyi V. Cinema in Ukraine (1896–1921): Facts. Films. Names / V. Myslavskyi. – Kharkiv: Torsing, 2005.

Myslavskyi V. N. History of Ukrainian Cinema 1896–1930: Facts and Documents / V. Myslavskyi. – Vol. 1. – Kharkiv: House of Advertising Publishing, 2018.

Berest B. History of Ukrainian Cinema / B. Berest. – New York: Shevchenko Scientific Society, 1962.

Rulin P. Maria Zankovetska: Life and Creativity / P. Rulin. – Kyiv: Rukh, 1929.

Durylyn S. M. Maria Zankovetska: 1854–1934. Life and Creativity / S. M. Durylyn. – Kyiv: Mystetstvo, 1955. – P. 450.

Kanivets A. Maria Zankovetska in the Context of Cinematography of the 1910–1920s / A. Kanivets // Yearbook of the Museum of Theater, Music, and Cinema Arts of Ukraine. Collection of scientific articles. – Issue 4. – Kyiv: 2021.

Vasylenko V. The Creative Path of M. K. Sadovskyi / V. Vasylenko // About M. K. Sadovskyi (Collection of Materials).

Veselovska H. The Cinematic Career of Mykola Sadovskyi / H. Veselovska // Ukrainian Week. – 11.12.2003. – Available at: https://tyzhden.ua/kinokar-iera-mykoly-sadovskoho/

Lykhachov B. Ukrainian Themes in Pre-Revolutionary Cinematography / B. Lykhachov // Kino. – №4. – Kharkiv: VUFKU, 1928.

Ginzburg S. Cinematography of Pre-Revolutionary Russia / S. Ginzburg. – Moscow: AGRAF, 2007.

The Great Cinema. Catalog of Surviving Fiction Films of Russia. 1908–1919. – Moscow: NLO, 2002.