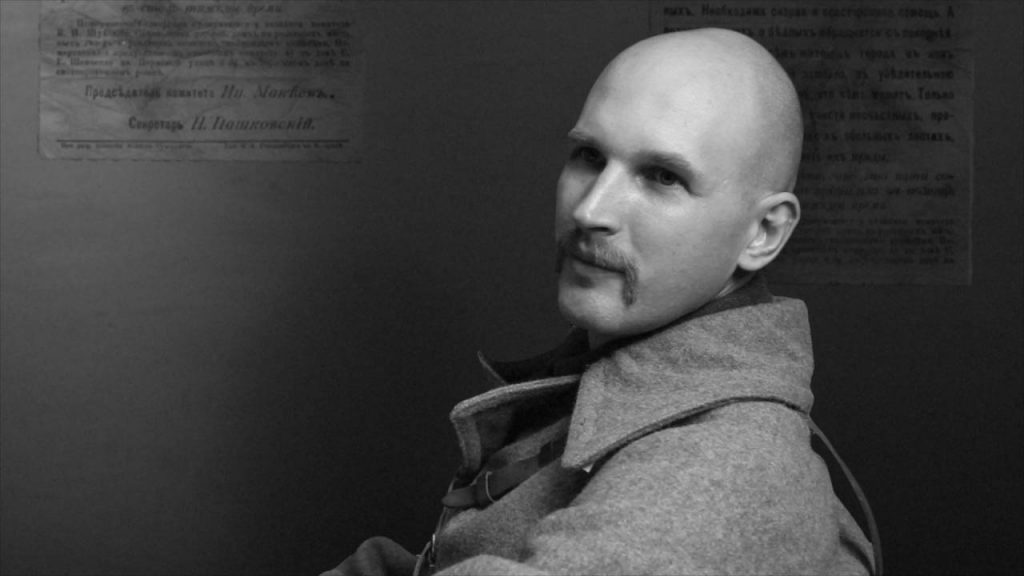

Vsevolod Petriv (Bohdan Ivanko)

Vsevolod Petriv, a colonel of the Tsarist Army, originally from Kyiv region, was the chief of staff of the 7th Turkestan Division during World War I. Later, he headed the Ukrainian regiment named after the Cossack Otaman Kostyantyn Hordiienko, held various positions under Hetman Skoropadskyi, headed the Zhytomyr Youth School, the Northern Division, the Volyn Group, the Military Ministry, and was Chief of the General Staff. Vsevolod Petriv had to witness many political intrigues, collect information about them, but beware of active participation in them.

The Seventh Turkestan Division, whose chief of staff Petriv was during World War I, occupied the most remote forested area, the so-called Nalibok Forest, covering an area of about a thousand square kilometers between the Neman and Berezina. It is significant that, against the background of the prevailing arrogance and arrogance of the officers, Petriv had good relations with the ordinary soldiers. After the outbreak of the revolution, the latter often turned to him for advice as their countryman. Perhaps that is why Vsevolod Petriv was elected to the divisional committee of the Turkestan Division and, as he wrote himself, "he treated his duties with respect, not joining any of the senior officers' groups and remained in the committee until the Ukrainians separated from the III. Siberian Corps". Having been forced to participate in the activities of committees and in corps and army congresses, Petriv knew well the moods of the new military life managers of the institutions, who considered themselves deputies of the "Savet of Saladniks and Workers' Deputies" (Petriv's spelling - author's note).

He took an active part in the formation of a separate Ukrainian regiment, which was perceived with great negativity by the leaders of both the Provisional Government and the revolution. Here is what the author himself writes about this: "At the time of the general breakdown, only the Ukrainians were different; they did not yet have the separations that ruined the Russian army; they still represented a single national collective; their officers were disgusted with any "officer's unions" and worked only in their Ukrainian communities along with their privates, and only this national unity was Bolshevism for some, counterrevolution for others." Nevertheless, Vsevolod Petriv actively declared his national position, he refused to take the position of division chief, arguing that "as a citizen of Ukraine, I cannot take over the leadership of the Russian army without the consent of the existing rightful Ukrainian government and therefore renounce not only the position of division chief, but also the position of chief of staff, which I had held until now." After this resonant statement, Petriv worked in the Ukrainian council, the division headquarters as a technical officer, and the corps committee, where there was a lack of qualified people. Being forced to travel a lot along the front, Petriv was a living link between all Ukrainian units that were denied access to information by the leadership.

Due to the lack of qualified personnel among the revolutionary military leadership, Vsevolod Petriv had to take part in peace negotiations with the German side as an expert (technical advisor) for the delegation of the Committee of the 7th Turkestan Division. By the way, the presence of a Ukrainian among the General Staff sincerely surprised the Germans, whose leadership mostly considered the Ukrainian idea to be a fiction.

After the situation at the front became critical for Ukrainian units, Vsevolod Petriv, together with the Kost Hordiienko Regiment, fought his way to Ukraine, where he took an active part in suppressing the Arsenal uprising in Kyiv. In fact, Petriv's regiment was one of the few well-organized and trained Ukrainian units that the Central Rada could rely on. Although Vsevolod Petriv himself did not always support the actions of the Ukrainian government. He was one of those who, from his own observations and communication with the villagers and ordinary soldiers, understood the situation in Ukraine well. Here is how the author of the memoirs describes it: "It was so difficult to imagine that it would be possible to do something with such a passive, disturbed people to restore their statehood, the lack of a sense of national community and national interests was so great at that time that one's hands would fall, the only thing that sustained them was the intuitive faith we felt in our villages in our Ukrainian government, the intuitive affection for our troops, who spoke in a "peasant" way, which we found everywhere and always in our difficult travels through "our land, not theirs." The villages near Kyiv, with which I had many connections at the time, because as a supporter of the territorial militia military system, I used the permission of the tsarist authorities to have 25% of territorial recruits in the army to make an attempt to at least partially socialize the army. Therefore, when I was in command of a company (for the purpose of the censorship as a senior officer of the general staff) in Kyiv, I established close ties with the relatives of my territorial soldiers to make the army less alien and hostile to them."

Vsevolod Petriv fought against the Bolsheviks throughout Ukraine with the Kost Hordiienko Cavalry Regiment, which was recruited in Kyiv after the alliance with the Germans, which, by the way, was not understood and supported by all of his soldiers. It is interesting to note that under Petriv's skillful leadership, despite constant fighting, the regiment's membership only grew. Already from Khorol, it set out on a campaign, "glittering with new weapons, showing off, on beautiful horses, in new wonderful hats, a quite impressive unit of four hundred men with guns, rapid-fire rifles, carts, communications equipment, behind which two light and three trucks rattle with their engines, and a Peugeot system on high wheels that can conveniently overcome the obstacles of bad roads."

With his regiment, Petriv reached the Crimea and even concluded an agreement with the Crimean Tatar republican government, which he reported to the Ukrainian leadership. But the latter, unfortunately, failed to orient itself in time and use the regiment's achievements. After the defeat of the UNR army, Vsevolod Petriv was interned in Poland.

Victoria Skuba based on materials by Vsevolod Petriv