Ukraine entered its independence filled with stereotypes about its history and culture. When I began studying film directing, we were taught a course on the history of cinema. At the time, Ukrainian cinema was believed to have started with VUFKU (All-Ukrainian Photo and Cinema Administration—a Soviet institution that operated from 1922 to 1930). According to some authoritative film scholars, this implied there was no Ukrainian cinema before the USSR. However, from our teachers of directing, I heard that something was indeed filmed before then. But what exactly? How did our cinema compare with global standards?

One teacher gave me a book by Volodymyr Myslavskyi, Cinema in Ukraine 1896–1921: Facts, Films, Names, which remains the most comprehensive collection of information about the early years of cinema in Ukraine.

Other facts can be found in contemporary periodicals and individual studies by other experts, such as the small Soviet-era monographs From the Past of Cinema in Ukraine, 1896–1917 by H. Zhurov (1959) and Pages from the History of Cinema in Ukraine by O. Shymon (1964). Unfortunately, most films from that time have not survived. In this fragmented context, such information is little known—not only to the general public but even to filmmakers, especially those who worked for russia until 2014.

Here, I will briefly outline key facts about the early achievements of Ukrainian cinema.

The First Film Recording

Everyone knows that the Lumière brothers invented cinema in 1895. However, their main achievement lies in transforming film screenings into public entertainment events. Actual film recording was conducted before them in nearly every developed country, where each had its own "inventor of cinema." For instance, the first filmed cats appeared a year before the Lumières "invented" cinema.

Ukraine had its own inventor, Yosyp Andriyovych Tymchenko (1852–1924). For many years, he worked as the chief mechanic of University in Odesa, with inventions spanning nearly all significant technical fields.

In 1893–1894, Tymchenko publicly demonstrated his developments in the field of cinema, showcasing two short films shot at a racetrack and presenting a device for projecting images at a scientific conference.

Film Declamations

Today, film declamations—a hybrid form of art combining the expressive power of theater with cinematic narrative—exist both as an art form and a method of training filmmakers and actors.

While examples of film declamations existed from the early 20th century, they became widespread closer to its mid-point.

In Ukraine, film declamations were actively created between 1909 and 1913, primarily by Oleksandr Oleksiienko, who also acted alongside his wife, Olena. What did these look like? On screen, action unfolded, while behind it, a choir performed the soundtrack, and actors voiced their roles. Creative tricks included carrying a bucket of hot coals into the hall to create the smell of smoke during a fire scene. The filming itself was relatively simple compared to contemporary European films, where declamations were less common.

Notably, these films often featured Ukrainian folk tales or popular theatrical plots, with the choir singing in Ukrainian.

According to Myslavskyi's calculations, 384 feature films were made in Ukraine by 1921. While we don't know how many were declamations, contemporary press reports suggest that few other types of films were made in Ukraine before 1913.

Structurally, declamations were proto-musicals in cinema.

From 1913, mass production of contemporary pan-Russian films began in Dnieper Ukraine (Western Ukraine has a separate history). These films were more expensive to produce but did not require paying a choir for each screening, making their distribution much more profitable. As a result, they quickly displaced film declamations from the market.

Zaporozhian Sich

In 1911, several important cinematic events in Katerynoslav culminated in the creation of the first Ukrainian historical blockbuster.

Local resident Danylo Sakhnenko, who advanced from mechanic to cameraman and director, founded the "Rodyna" film studio (deliberately or inadvertently mimicking Mykola Lysenko's patriotic double entendre: "rodyna" means "family" in Russian but "homeland" in Ukrainian).

He filmed two plays by Mykola Sadovskyi's theater—Naimychka by I. Karpenko-Karyi and Natalka Poltavka by I. Kotliarevskyi.

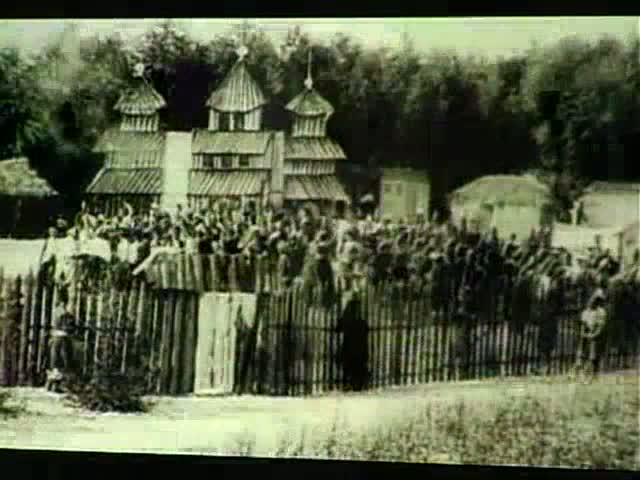

More importantly, he produced the first Ukrainian feature-length film, Zaporozhian Sich. This film depicted the heroic 17th-century campaigns of Zaporozhian Cossacks led by Ivan Sirko. Filmed in September 1911 in Lotsmanska Kamianka, it involved over 400 participants, including Cossack descendants. Historical consultant Dmytro Yavornytsky provided authentic Cossack costumes. Special decorations and music were created for the film, and local residents helped gather clothing, props, and create mock weapons. The film premiered in January 1912. Only four frames have survived to this day.

The film was highly successful, paving the way for historical dramas such as Andrii's Love (based on Taras Bulba), Mazepa (based on Pushkin's poem), and Bohdan Khmelnytsky (based on Mykhailo Starytskyi's works).

Presentation

Ukrainian cinema did not lag behind. Limited in funding, our filmmakers maximized their available resources.

This new art form, not yet officially recognized as such, existed on the fringes of Russian censorship, allowing Ukrainian themes to be explored. These themes supported our culture and awakened consciousness in a generation of viewers that would soon fight for freedom—a separate story altogether.

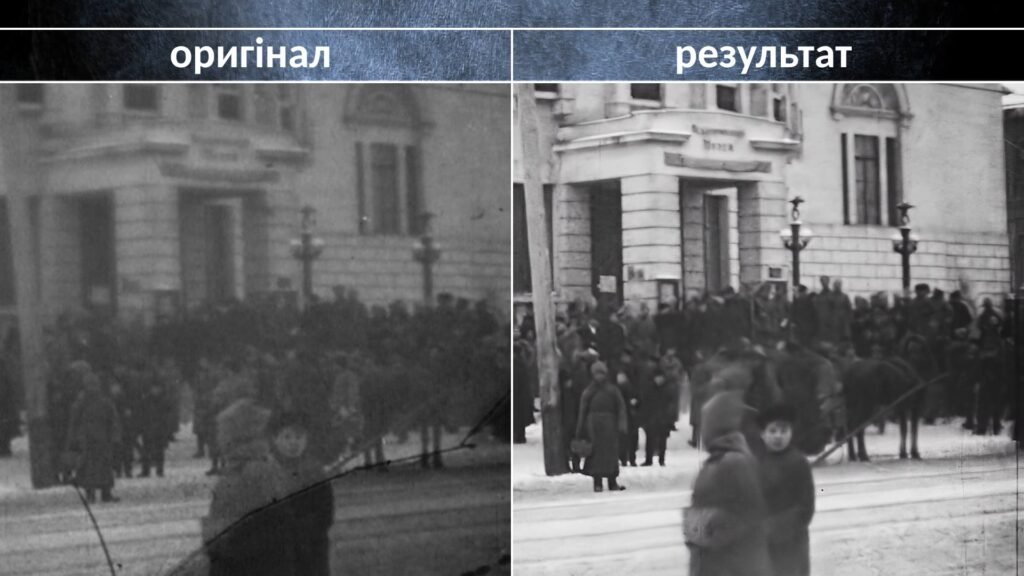

Cinema, particularly newsreels, preserved living portraits of people who shaped Ukraine's history of independence over a century ago. If you want to see these people on the big screen, we invite you to the presentation of the 1917 film Ukrainian Movement, which contains unique footage from the Ukrainian National Revolution. This documentary, showcasing Mykhailo Hrushevskyi, Volodymyr Vynnychenko, and others, is one of the few cinematic records of that era. Stored in the Central State Archive, the film underwent numerous duplications that degraded its quality. Our team restored it using 4K and AI technologies.

The restored film and details of the restoration process will be presented on November 26 at 6:00 PM in the Blue Hall of the Cinema House in Kyiv.