Part I. The aesthetic. How masterpieces are born... or not born

‘Art beyond politics’ has by now become a meme. Yet those who remember — or have studied — the Soviet Union know that art there acquired a political coloring even regardless of the author’s intent. The story of Parajanov is perhaps the most vivid example of this.

It all began peacefully. The year 1964 was approaching — the centenary of the birth of the classic of Ukrainian literature, Mykhailo Mykhailovych Kotsiubynsky. Traditionally, such anniversaries were marked with a series of celebrations, including film adaptations — such films were jokingly called ‘anniversary films.’ And so, at the end of 1962, the writer’s daughter, Iryna Kotsiubynska, director of the Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky Memorial Museum in Chernihiv, wrote a letter to the Kyiv-based O. Dovzhenko Film Studio requesting a screen adaptation of his novella Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors for the jubilee. The studio agreed: they saw nothing subversive in the plot, and even the mandatory class conflict of those times was present. For the production, they chose the mediocre director Serhii Parajanov, who was expected to shoot yet another routine film and ‘tick a box’ in the studio’s plan.

What could possibly go wrong? And yet — there was Kotsiubynsky’s novella, there were the Carpathians, there was a unique film crew: screenwriter Ivan Chendei, cinematographer Yurii Illienko, artist Heorhii Yakutovych, composer Myroslav Skoryk, and a brilliant cast, with Ivan Mykolaichuk in a special role. And finally, the Hutsuls, who appeared not only as extras but also as consultants for the film. Thus the ‘anniversary film,’ yet another classic on screen, unexpectedly turned into an aesthetic explosion that revealed a new Parajanov. Moreover, it was the very explosion that laid the foundation for a new author-driven Ukrainian cinema, which came to be known as ‘Ukrainian poetic cinema.’

At the time of filming "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors", Serhii Parajanov had already been working at the Kyiv film studio for nine years (he had been sent there directly after graduating from VGIK) and had shot several documentaries and feature films in different genres: the comedy "The First Lad", the wartime musical drama "Ukrainian Rhapsody", and"the "miners" film "Flower on the Stone". All of them were below the studio’s average level, which is why Parajanov’s work is clearly divided into ‘before Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors’ and ‘after.’ From time to time, researchers examine his early films with a magnifying glass, trying to find glimpses of the future, the ‘real’ Parajanov — and, at the same time, to unlock the mystery of the magic of "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors". In particular, film scholar Olha Briukhovetska points out that Parajanov’s thinking was rooted in visual imagery: he was a master of images rather than narrative. That is why the most ‘Parajanovian’ moments — the flashes in his films, such as the lovestruck shopkeeper throwing veils over his beloved in "The First Lad", or the soldier playing the piano in a ruined church in Ukrainian Rhapsody — remain at the level of individual frames. In his early films, he was groping for his artistic language, his creative mode — and he found it precisely in Shadows, through the material of archaic Hutsul culture, whose world he managed to recreate in a figurative, poetic, and painterly key.1.

“As soon as I began to read Kotsiubynsky’s novella, I wanted to stage it,” the director recalled. “I fell in love with that crystal-clear sense of beauty, harmony, infinity. The sense of a boundary where nature turns into art, and art into nature.”2. In fact, that idea of ‘nature turning into art, and art into nature’ is essentially the formula of his film. And traditional culture, which effectively becomes the film’s protagonist, is in a sense that very point of intersection between art and nature. This is precisely what fascinated Parajanov about the Hutsuls: he spoke with delight about his experience of interacting with them, admiring their natural ease and their childlike, fresh outlook on the world3. One could say that this trait was also close to Parajanov himself: he, too, amazed those around him with his free, open-to-the-world perception of beauty. The director was struck by the unity of the Hutsuls with nature, with their environment: wooden architecture derived from the ‘architecture of forests and mountains4— the trembitas that echo the sound of the mountains, their mastery in working with wood and handling the axe, their skill in crossing turbulent rivers, even the remnants of paganism — the cult of nature and the spirits inhabiting it. Parajanov infused all of this into his film.

This approach was highly uncharacteristic of Soviet cinema: as a rule, folklore and ethnography served merely as a wrapper for stories constructed according to ideological canons. Hence the artificiality and contrived nature of folk culture in most films, where peasants looked more like members of folk ensembles. Moreover, as Joshua First aptly observed, back in Stalin’s times folkloric images in cinema had already been stereotyped and standardized: they seemed to point to ethnic differences, yet never went beyond the framework of socialist realism. Traditionally, representatives of different nationalities were depicted through a handful of stereotypical, easily recognizable traits: for example, the Ukrainian on screen would wear an embroidered shirt, while the Georgian would perform a lezginka dance.5. In the Thaw era, the situation began to improve, yet the device — along with the imperial narratives embedded in it — did not disappear, remaining in force until the decline of the Soviet era, and even beyond it.

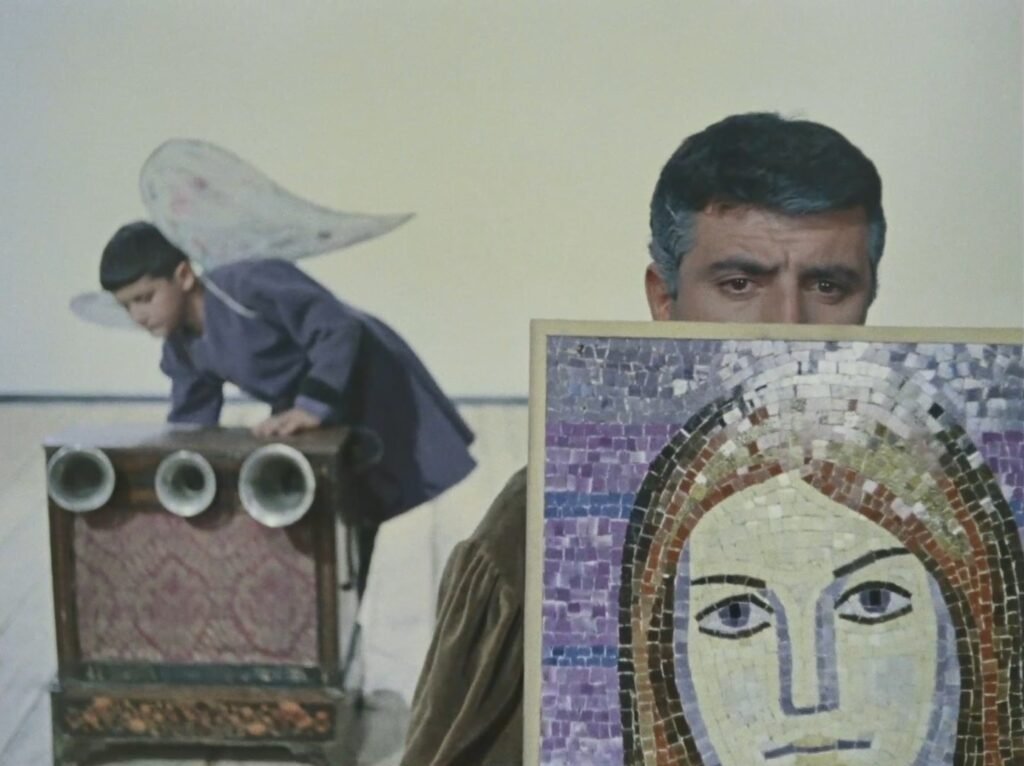

Parajanov took a fundamentally different path: he depicts the very force of traditional culture, untamed and unconstrained by stereotypes. In many ways, the material itself helped him — the Hutsul region, lesser known and almost ‘exotic’ even within Ukraine. In Parajanov’s portrayal of this world, authenticity — or its illusion — takes a central place. In his article Eternal Motion, he spoke about this: ‘We very quickly realized that any cinematic imitation, any stylization — much like how Ancient Rus, Ancient Rome, or Ancient Egypt is often recreated — would be offensive here.’6. His sensitivity here was so strong that he could introduce something of his own without disturbing the overall picture. As he wrote in the same article Eternal Motion: ‘I realized while working on Shadows that perfect knowledge justifies any creative intent. I could transform song material into action, and action into song… I could turn ethnographic or religious material into the most mundane, everyday form.’ He gives as an example the ‘yarmo’ ritual in the Hutsul wedding ceremony, which in fact does not exist. ‘I heard a song (a kolomyika) about a man putting his wife into a yoke — an allegory, as if it signified an unequal marriage. And when my Ivan marries Palagna, I conducted the “yarmo ritual” over them. And the Hutsuls who acted in my film performed it as seriously and beautifully as all their traditional rituals.’7This is perhaps the most famous example of Parajanov transforming source material — yet in "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors", everything still remains within the framework of the depicted culture. In "Sayat-Nova", he already openly moves into the language of metaphors and symbols, and in "Ashik-Kerib", at times he boldly mixes elements of Western culture and even modernity into the imagery of the old Azerbaijani world. But in all cases, Parajanov demonstrates masterful, original handling of a given national culture. And in every instance, the culture tends to dominate the plot, rather than the other way around.It goes without saying that in all these cases, there was no place for Soviet ideology in the colorful world presented to the viewer. Another very telling episode worth mentioning is the story of the dubbing of "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors", or rather, its absence. At that time, films were either dubbed into Russian or shot directly in Russian — an approach that, of course, had an economic rationale (a film in the ‘common understandable language’ could be shown across all republics, generating the corresponding box office revenue). More importantly, this ‘commonality’ also signaled belonging to the shared Soviet space: one language — one territory — one people.Parajanov refused to dub "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors" for artistic reasons: the Hutsul dialect is a key element of the film’s soundscape, and without it, the film is perceived differently. Language in cinema truly matters: one need only recall the sensation caused by the discovery of the original Ukrainian audio track in the comedy "Chasing Two Hares". And it’s not only that each re-voicing introduces subtle shifts in the perception of the film — what mattered was that the Ukrainian original seemed to affirm the film’s ‘Ukrainianness,’ its belonging specifically to Ukrainian, rather than Soviet, cinema.

‘Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors’ became a manifesto. In the apt words of Leonid Alekseichuk: ‘A quarter of a century before the Ukrainian parliament, Parajanov fearlessly proclaimed an idea that at the time was automatically branded as a criminal, anti-Soviet, bourgeois, and fascist: Ukrainian independence — Ukrainian aesthetic independence.’8.

So, how exactly did this manifesto take place — and how was it received by the cinematic community, particularly the film bureaucracy? It should be noted that at that time, for a film to be released, it had to pass through a whole series of hurdles in the form of artistic councils at various levels and at different stages of production. Finally, the finished film also had to be approved in Moscow. All of these stages, of course, applied to "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors".The screenplay by the Transcarpathian writer and folklorist Ivan Chendei was accepted favorably, though, as was customary, certain comments were made — in particular, regarding the extensive scenes of religious rituals (highly undesirable in the atheist cinema of an atheist state) and the lack of depiction of social motives (highly desirable in the socialist cinema of a socialist state). In Moscow, the revised and supplemented script was met with a series of additional comments, including that the “theme of the Hutsuls’ labor life was not revealed deeply or consistently enough”; it was also recommended that “in the folkloric material… whenever possible, emphasize the real sources of its origin.”9. All of this — nuances that, however, already hinted at the film’s future priorities: portraying the Hutsul world from ‘its own perspective’ and disregarding certain elements that were mandatory for a Soviet film.

Later, during the filming period, another problem emerged: the clash of two creative personalities, a struggle over the film’s aesthetic vision between director Serhii Parajanov and cinematographer Yurii Illienko, actively fueled by the strong temperaments of both. This conflict spilled over into production documents titled ‘On Abnormal Working Conditions in the Production of the Film "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors"’ (from October 1963) and ‘On the Unsatisfactory Work of the "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors" Crew’ (from December 17, 1963).It reached the point where both parties were formally reprimanded, and the rebellious Illienko was replaced by Suren Shakhbazyan. There were complaints about falling behind schedule, overspending, and the director’s inability to organize the crew and maintain good relations — though the artistic value of the future film was never questioned. Another very characteristic remark was that the script was being changed ‘toward emphasizing not social, but everyday-ethnographic elements.’ The leadership again issued reprimands and tasked the team with preparing materials for review at the studio to decide the final fate of the crew.All of this drama unfolded against the backdrop of the Carpathians, where the crew went to shoot, working under difficult and sometimes dangerous conditions. The material presented to the studio elicited admiration — but also some concern: the creators were reminded once more that ‘"Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors" is not an ethnographic or romantically exotic work, but a work based on Kotsiubynsky, deeply social.’The finished film was received at the Dovzhenko Studio with enthusiasm; despite the usual minor comments, the recurring sentiment was that the film was a triumph, a celebration for both the crew and the entire studio. However, among party officials, the film provoked some caution; a telling remark concerned a ‘miscalculation of the cementing idea’ in the film.10.

The next film — based on fundamentally new, urban material — was to be "Kyiv Frescoes". The concept was ambitious: to depict nothing less than the ‘soul of Kyiv,’ the life of the city in an inseparable connection between past and present. It was to be a film about time — in the director’s words, ‘a great architect who constantly reconstructs, restores, destroys, adds… capturing the layers of history, returning us to primordial truth.’11. In this film, a particular challenge — an aesthetic challenge — came from the script itself. During its discussion at the studio, there were mixed feelings: admiration for the complex, refined material and for the sheer scale of the concept on one hand, and concern over the challenging form on the other. Terms like ‘experiment’ and ‘search’ were used to describe the text, conveying excitement mixed with a certain caution: the approach to the script’s form was daring, and the result could be unpredictable. Nevertheless, the script-editing board accepted the literary script with a favorable, even enthusiastic, response.12The director’s version of the script was received less warmly; incidentally, it was then that the director described it as ‘poetic cinema, which is asserting its right to exist at the Kyiv Film Studio.’ On the other hand, voices began to be raised that the text was complex and even ‘formalistic’ — a practically derogatory term since the 1930s, one that could have effectively ‘killed’ the film. The writer Yaroslav Bash, a member of the artistic council, even remarked in a very socialist-realist spirit: ‘There is a law of art: incomprehensible art is no longer art.’ Another pejorative term was used: ‘abstractionism.’ Parajanov responded to these criticisms: ‘God grant that our studio be accused of formalism. God grant that we have symbols. Dovzhenko relied on symbols.’13. Ultimately, the script was accepted, though not without a number of fundamental comments listed in a subsequent review: ‘The issue concerns the discrepancy between the task set by S. Parajanov — to depict the image of contemporary Kyiv — and the purely subjective, at times painful and whimsical authorial perspective on the life and people of the city — the capital of Soviet Ukraine; the demonstrative obscurity, or even absence, of a central idea that would unite the disparate episodes; and the excessively complex artistic language of the script. "Kyiv Frescoes" was included in the plan of the O. P. Dovzhenko Film Studio on the condition that images and episodes be added to the script to make the theme and idea of the work perceptible and clear, and that a number of conflicting or inappropriate images and situations be removed from the material (cemetery, the deaf-mute people near the Eternal Glory monument, etc.).’14. So, ‘clarity’ of the film; a clear theme and idea; God forbid, no ‘conflicting images and situations’ — this was what was expected of a proper film by a proper director. Separately, there was concern about the insufficiently ‘life-affirming orientation of the future film.15. So, if "Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors" was already moving away from socialist realism, then "Kyiv Frescoes" left no stone unturned — except for the recurring theme of ‘Victory Day,’ which, of course, was warmly received by administrations at various levels. The State Committee of the Council of Ministers of the Ukrainian SSR for Cinematography — the equivalent of the Ministry of Cinema at the time — ordered the corresponding changes to be made to the script. The changes were made, but the complex, ‘formalistic’ film never saw the light of day.From the screen tests for "Kyiv Frescoes," Parajanov, together with his regular editor Maria, assembled a short film; after his arrest, the film was considered lost, until 1992, when a copy of the screen tests for "Kyiv Frescoes" was found in the safe of the film archive at the O. Dovzhenko Studio. Apparently, the reel was saved because cinematographer Oleksandr Antypenko had used it as a diploma project. In 1993, at a memorial evening for Serhii Parajanov, the screen tests for "Kyiv Frescoes" were shown again.16 And since then, they have been shown regularly — proving that art is not so easy to destroy.

In 1970, Parajanov submitted the script for "Intermezzo" to the studio — yet another homage to Mykhailo Kotsiubynsky, who had once brought him creative triumph. The refined, impressionistic script, expressed in a visual form, explored the writer’s inner world — and again, it did not fit into the frameworks of socialist realism.Commenting on the script, the script-editing board criticized it for insufficiently reflecting the impact of the 1905 revolution’s defeat on the artist’s soul, and for a scene of a meeting with a woman, which again did not correlate with the devastation in his soul that this defeat was supposed to bring. They also pointed out ‘modernist symbolism’ and even a ‘Kafkaesque aesthetic,’ as well as ‘subjectivism, with extremely coded symbolism, which in this case is far from the realistic symbolism of M. Kotsiubynsky.’It is impossible not to mention a very telling phrase by one of the leading Ukrainian Soviet directors, Tymofii Levchuk: ‘A film must be made for the general audience, and this film must be understandable to everyone.’17 In essence, this is the quintessence of a kind of mass-culture understanding of socialist realism — which, however, was shared by many.

One of Parajanov’s ideas was rejected after another… According to Leonid Cherevatenko, when he expressed sympathy to Parajanov, the director replied: ‘Ha! It would be worse if they liked it. Don’t you understand: they fear not my scripts, but my way of thinking’ — and this referred not only to the film authorities, but also to the average Soviet viewer in general.18Later, Ivan Dziuba published a letter from Parajanov to the Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Ukraine, Fedor Danylovych Ovcharenko, in which he listed, among other things, his unrealized projects: ‘Not only did I not receive any commissions, but my own initiatives — attempts to make the films "Kyiv Frescoes," "Confession," "The Fountain of Bakhchisarai" — were constantly rejected. And my theatrical plans (I wanted to stage "Hamlet," work with the experimental youth theater organized at the studio) — there’s no point even mentioning them. For five years now, I haven’t made a single film at the Kyiv studio. In essence, I have been artificially, administratively, and discriminatorily removed from any creative life of the collective.’19.

1 Briukhovetska O. PARAJANOV’S METAMORPHOSES: FROM VERSIFIED FILM TO CINEMA OF POETRY. НАУКОВІ ЗАПИСКИ НаУКМА. 2016. Том 179. Теорія та історія культури. С. 50-56.

2 Параджанов Сергей. Вечное дивижение. Искусство кино. №1, 1966. С. 62.

3 Параджанов Сергей. Вечное дивижение. Искусство кино. С. 64.

4 Параджанов Сергей. Вечное дивижение. Искусство кино. С. 64.

5 Joshua First.; Ukrainian Cinema : Belonging and Identity During the Soviet Thaw. P. 30.

6 Параджанов Сергей. Вечное дивижение. Искусство кино. С. 63.

7 Параджанов Сергей. Вечное дивижение. Искусство кино. С. 63.

8 Leonid Alekseychuk. A Warrior in the Field. Sight and Sound INTERNATIONAL FILM QUARTERLY WINTER 1990/91 VOLUME 60 No 1. Р. 23.

9 Р. Корогодський. «Рік життя біля джерела натхнення» // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 63.

10 Р. Корогодський. «Рік життя біля джерела натхнення» // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 70-95.

11 Параджанов Сергей. Вечное дивижение. Искусство кино. С. 66.

12 Матеріали до історії створення сценарію «Київські фрески». Протокол обговорення літературного сценарію С. Параджанова «Київські фрески» від 24.11.65 // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 111-114.

13 Стенограма засідання художньої ради Київської кіностудії художніх фільмів ім. О. П. Довженка

(обговорення режисерського сценарію С. Й. Параджанова «Київські фрески») 9.VI1.1965 р. // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 121-132.

14 Постанова Державного комітету Ради Міністрів УРСР по кінематографії № 58 від 13.1X. 1965 р. «Про режисерський сценарій С. Параджанова «Київські фрески» // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 141.

15 Там же, с.142

16 СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 148.

17 Лист сценарно-редакційної колегії № 312-1139 від 13 жовтня 1970 р. // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 169-174.

18 Л. Череватенко. Провісник. // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 272.

19 Дзюба Іван, Дзюба Марта. Сергій Параджанов. Більший за легенду – К.: АУХ І ЛІТЕРА, 2021. С. 137.

1 thought on “Сергій Параджанов і його українське кіно: як естетичне стає політичним. Частина І.”