In 1921, the People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs, Dmytro Manuilsky, offered the young civil servant Oleksandr Dovzhenko a diplomatic position. The future film director (who did not yet know this about himself) wanted to pursue an artistic education—specifically in architecture—so he was “enticed” with the possibility of obtaining it abroad. As Dovzhenko would later write in his Autobiography, the People’s Commissariat of Education, having learned of his love for painting, specifically recommended him for work to Oleksandr Shumsky, then the representative of the Ukrainian SSR in the Republic of Poland, precisely so that the gifted young man could use the trip abroad to study art. Dovzhenko took little interest in diplomatic work, and as soon as he got the chance, he abandoned it.1. He first worked in Poland, and then, in February 1922, was transferred to the General Consulate in Berlin.2 to the position of secretary—a lower rank, but within three or four months he received a scholarship from the People’s Commissariat of Education and began studying at a private art school, with the aim of later entering the Academy of Arts in Berlin and Paris.3. In his Autobiography, Dovzhenko writes that he resigned from service; according to the research of Vasyl Marochko, in the summer of 1922 the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine decided on a kind of reshuffling of the diplomatic corps—likely to replace the Borotbists in the Berlin mission with Communists. Yet, at Dovzhenko’s request, he was allowed to remain in Berlin to continue his art studies.4.

As we can see, at least outwardly, this story is almost a textbook example of social mobility. A former Petliurist receives a diplomatic post without any effort—in fact, it is offered to him—and afterward he gains the chance to study art abroad and even plans to enter an academy. True, this window of opportunity closes rather quickly, but it perfectly conveys the spirit of “our 1920s,” with their dynamism and openness to new experiences. Dovzhenko’s diplomatic career is often linked to the influence of the Borotbists, including Oleksandr Shumsky.5.

During his Berlin period, Dovzhenko entered into close contact with artistic circles—not only German ones. In particular, he met Oleksandr Arkhypenko and struck up a friendship with Mykola Hlushchenko. According to the painter’s recollections, Dovzhenko often came to his studio and would stay late into the night. At first he only observed, but soon he began to paint himself. He constantly studied the theory and practice of painting and worked on self-improvement.6…

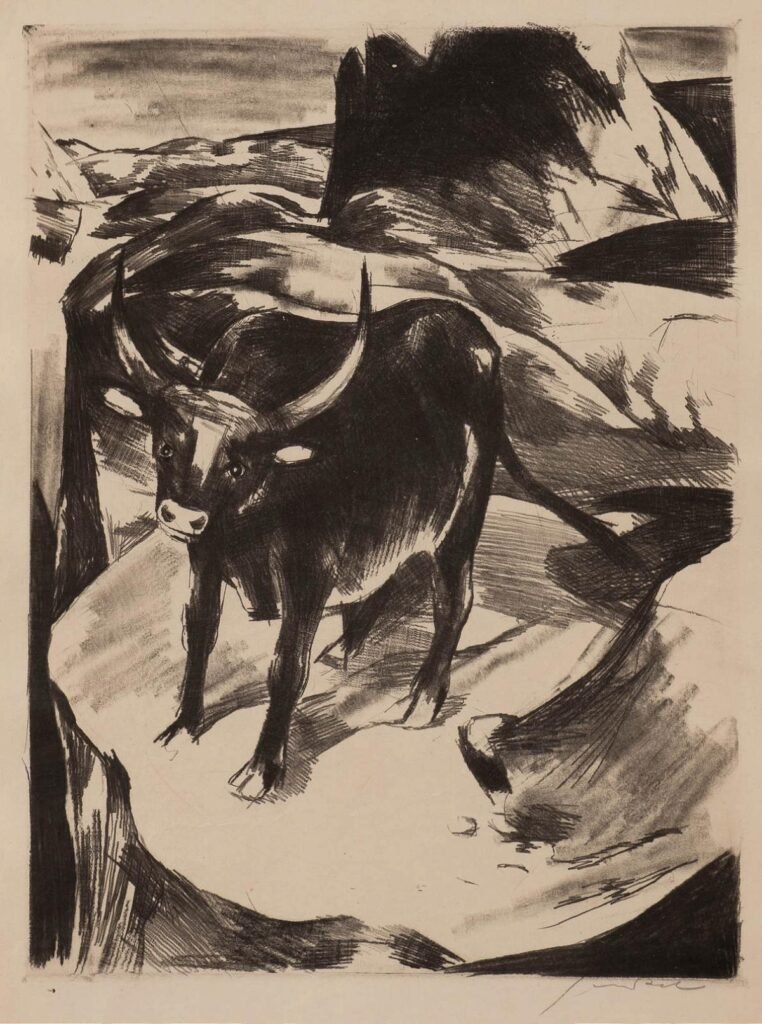

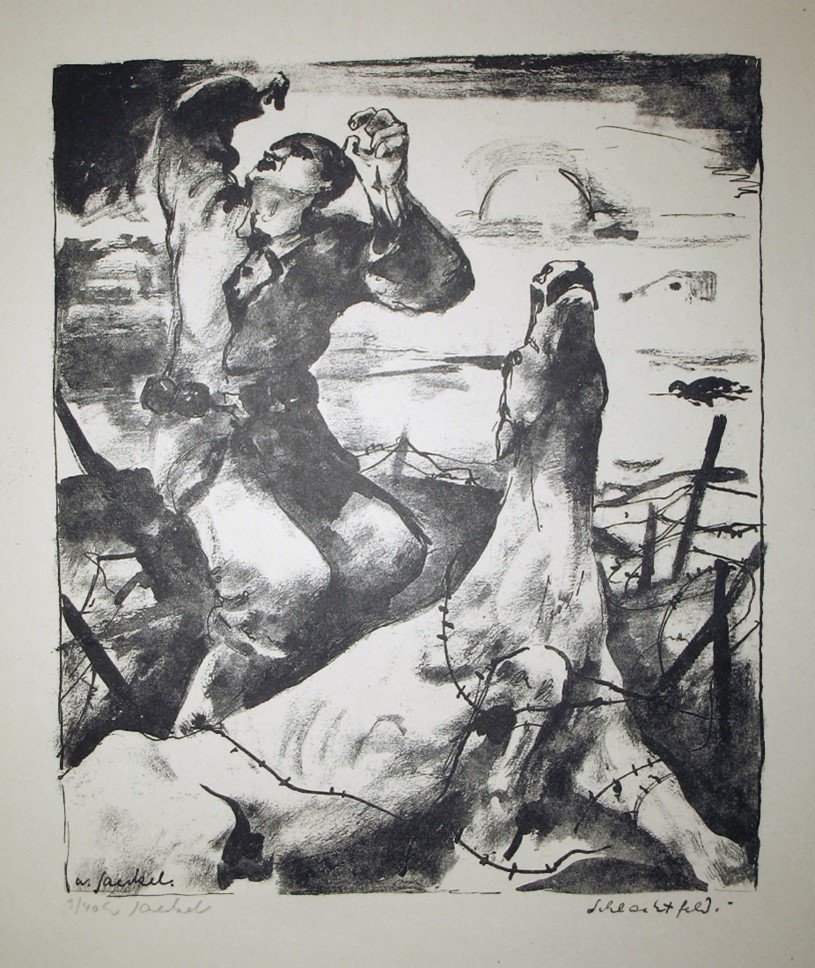

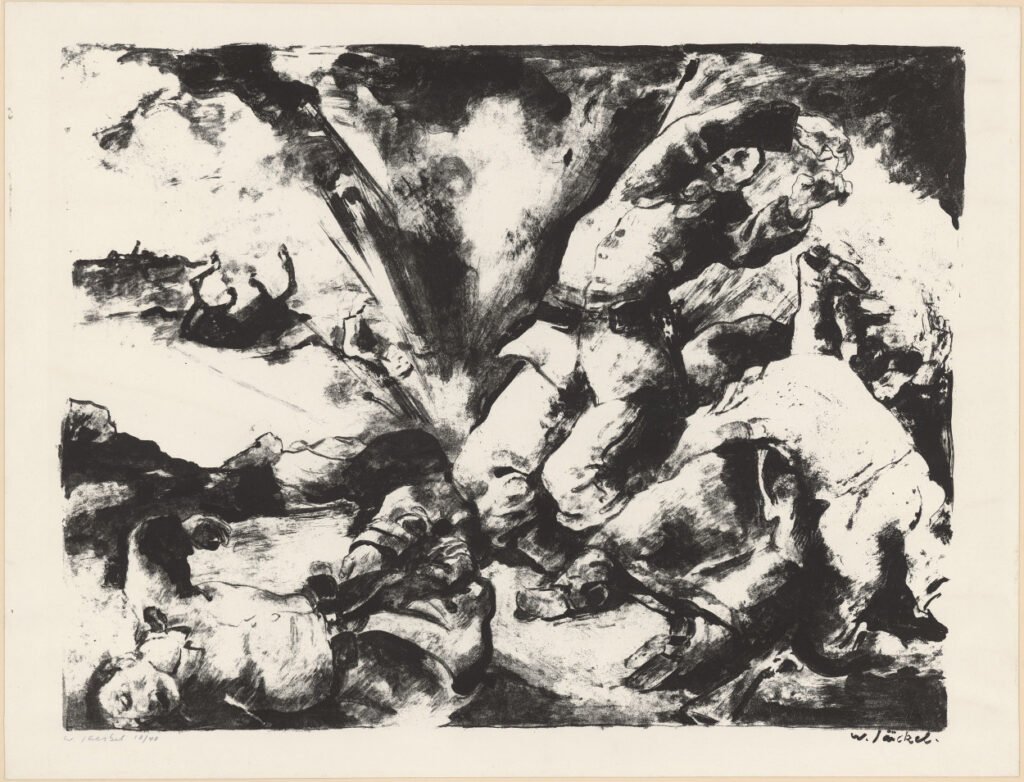

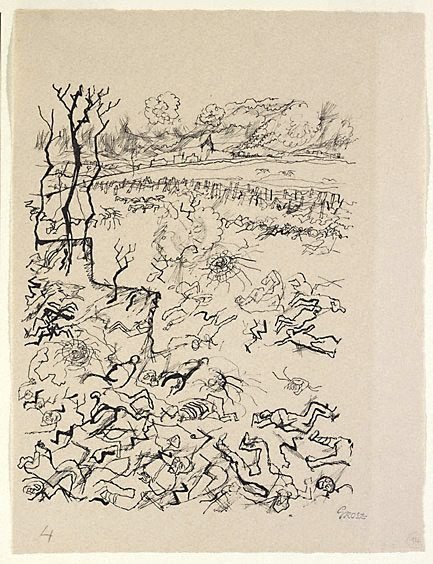

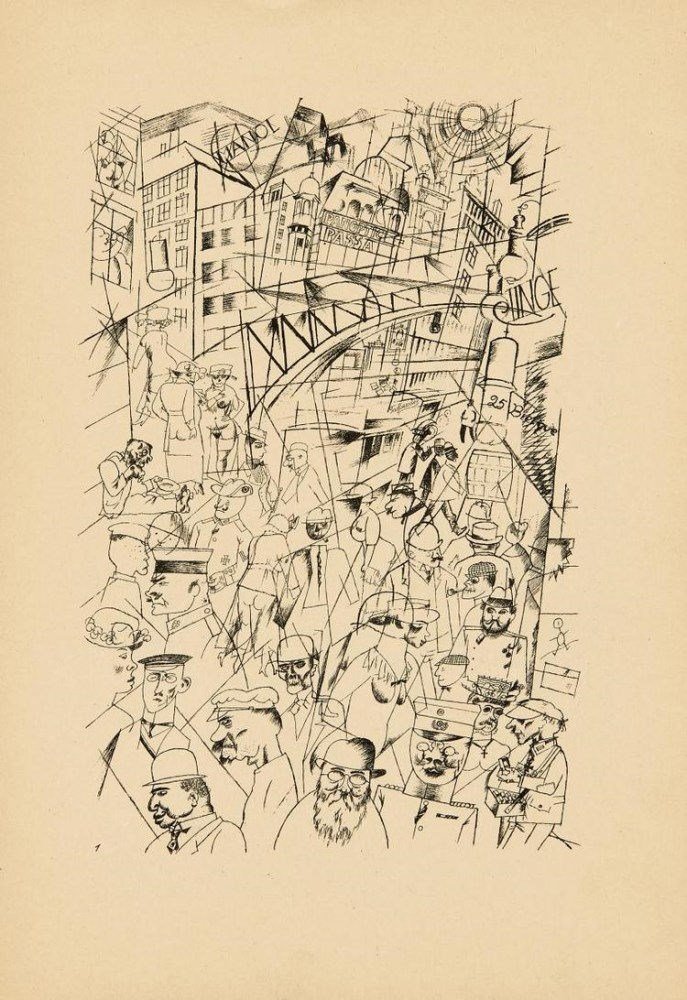

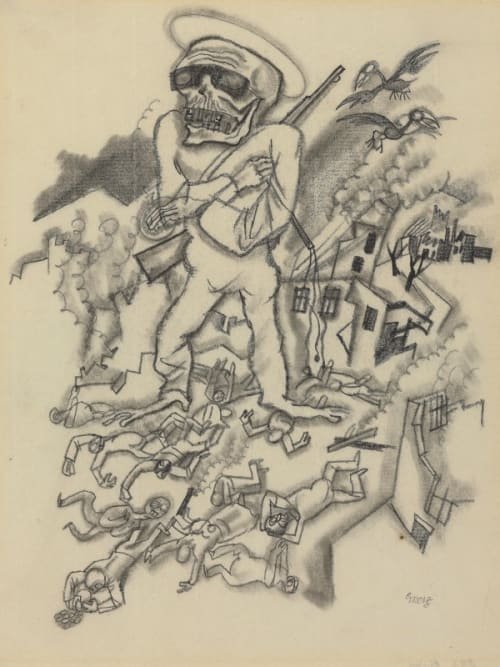

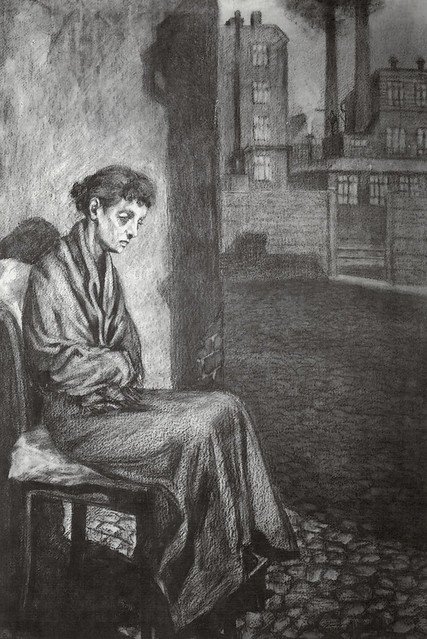

The German film scholar Georg-Joachim Schlegel, who wrote a fairly detailed study on Dovzhenko’s time in Berlin, lists the artistic institutions and associations where the future film classic acquired his knowledge: the State Higher School of Arts under Professor Arthur Kampf, the studio of Hans Baluschek, who also helped him enroll as a guest student at the Berlin Academy of Arts. Dovzhenko was also a guest student at Flora-Komplex in Charlottenburg (part of the former Royal Institute of Glass Painting), which would later influence the floral motifs in his films.He actively interacted with artists: participating in discussions of the Künstlerhilfe association, attending art exhibitions, meeting Heinrich Zille, Käthe Kollwitz, Otto Nagel, and befriending Georg Grosz. He also took part in student exhibitions at art schools, where he caught the attention of Professor Gerhard Janensch of the State Higher School of Fine Arts, who recommended him to the well-known Casper Gallery on Kurfürstendamm, where Dovzhenko was then living. Janensch also helped him enroll in the school of expressionist painter and graphic artist Willy Jaeckel.7Incidentally, the latter had participated in the First World War, had been to Russia, and spoke a little Russian.8. At the beginning of the war, he managed to publish an anti-war series of lithographs, Memento mori, which quite possibly influenced Dovzhenko’s Arsenal. According to Alfred Krautz, who researched and confirmed that Jaeckel was indeed Dovzhenko’s teacher, the artist’s work contains several distinct motifs that later appear in Dovzhenko’s films: humans within nature, landscape motifs featuring the sun and rainbow as symbols of peace and fertility, images of grandfathers, battle scenes, and portraits.9.

Dovzhenko also developed connections in theater and cinema: for example, at one exhibition Grosz introduced him to Hans Klering, an actor with the Kolonne Links troupe, who later emigrated to the USSR and, incidentally, appeared in the film "Shchors."10Dovzhenko made contacts with the popular film director Ernst Lubitsch, who introduced him to Fritz Lang, Georg Wilhelm Pabst, Friedrich Murnau, Emil Jannings, Paul Wegener, Pola Negri, and others. Dovzhenko was also a frequent guest at the home of Asta Nielsen, whose husband was another well-known actor, a native of Poltava, Hryhorii Khmara.11.

In July 1923, he returned to Kharkiv. As Yuri Yanovsky wrote in his In November: “From Berlin, my friend brought the calm manners of a great city and a few gray hairs at his temples.” Dovzhenko would return there a few years later, both as a guest and as one of the leading Soviet film directors. He arrived in June 1929, when his films Zvenyhora and Arsenal were being shown at the Ukrainian Soviet Industrial Exhibition.However, there were some problems: at that time, copyright relations were much more relaxed, and it was common for distributors to re-edit purchased films. In Dovzhenko’s case, the distribution company Prometeus, associated with Communist circles, combined his films into one for commercial reasons, ignoring the director’s protests.A year later, in July 1930, Dovzhenko visited Berlin again. This time his film Earth was being shown—and again there was a scandal, this time of an ideological nature. Because of the stance of Prelate Winken, a member of the Berlin censorship commission, the film, deemed offensive to the feelings of believers, was only allowed a restricted screening. It could be seen by a “narrow circle of individuals” who “had special passes as representatives of the film industry, the film press, and the daily press.” Within this circle, the premiere took place on July 4 at the Marmorhaus cinema on Kurfürstendamm.In his speech, Dovzhenko complained about censorship and shared his own vision of spatial evolution in cinema—deepening perspective (a thoroughly Renaissance idea!). He later elaborated on his creative ideas in specialized articles, primarily for Reichsfilmblätter.12. As for the Berlin critics—they received the film with enthusiasm and condemned the clerical censorship. Later, in November, the German League of Independent Cinema managed to secure the right to screen Earth—with cuts for a young audience and uncut for adults.13.

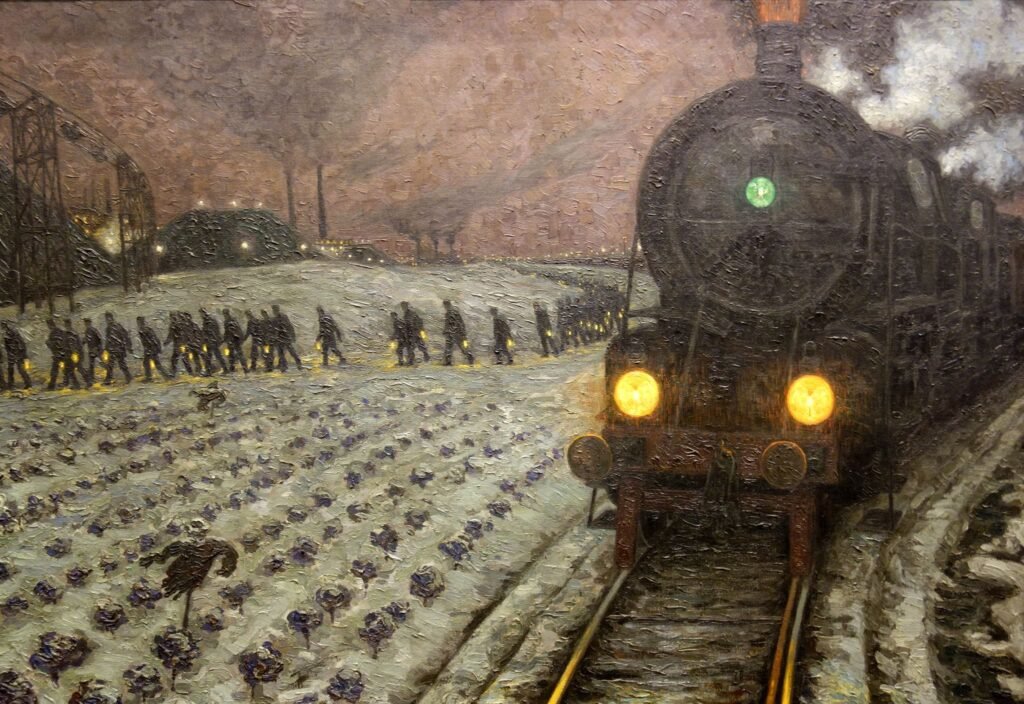

The Berlin period was not only about studying; it was also Dovzhenko’s entry into the Western European cultural context. Fritz Lang’s "Nibelungen," with its monumental style, could very well have influenced "Zvenyhora," while "Arsenal" was created according to the principles of Expressionism—both in its worldview and its artistic language.14. Direct references to German visual art, especially Expressionism, can be found in his films: the famous scene with the soldier poisoned by gas in "Arsenal" recalls the graphics of Georg Grosz, while a shot of a mother and child evokes Käthe Kollwitz.15Researcher Julia Sutton-Mattocks, in particular, has studied in detail the references in "Arsenal" to Käthe Kollwitz’s series "The Weavers’ Revolt" (1897) and Willy Jaeckel’s "Memento 1914/1915" (1915), as well as to the works of Francisco Goya and Otto Dix.16.

As we can see, Oleksandr Petrovych was not only a great Ukrainian but also a great European. The "Berlin" period of his life, brief as it was, became a true artistic—and more broadly, cultural—school for him. What would "Zvenyhora," "Arsenal," and even "Earth" have been like without those short eighteen months in one of the world’s cultural metropolises? Who knows, who knows…

А за кілька десятиліть Довженко повернеться до Берліна знову – вже в символічному вимірі. Про те, як Берлін згадуватиме Довженка і яких форм ця «дружба» набуде після повномасштабного вторгнення – ми розкажемо у другій частині статті.

1 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 45-46.

2 Іоахімстальштрассе, 37.

3 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 45-46.

4 Марочко В. Книга «Зачарований Десною. Історичний портрет Олександра Довженка». Видавничий дім “Києво-Могилянська академія”, 2006. С. 58-59.

5 Марочко В. Книга «Зачарований Десною. Історичний портрет Олександра Довженка». Видавничий дім “Києво-Могилянська академія”, 2006. С. 53.

6 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 46.

7 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 46.

8 Олександр Довженко: між тоталітаризмом і національною ідеєю. енциклопедичний словник. т. 1 : а–л / [голов. ред. Г. Скрипник; відп. ред. С. Тримбач]; Інститут мистецтвознавства, фольклористики та етнології ім. М. Т. Рильського НАН України. Київ, 2023. С. 139-140.

9 Альфред Крауц. Як починався митець… // Довженко і світ: Творчість О.П. Довженка в контексті світової куль- тури: [упоряд. С. Плачинда]. – К., 1984. С. 14-15.

10 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 46.

11 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 46-47.

12 Статті «Справжній автор фільму» 1930 р., «Робота з непрофесійним виконавцем» 1931 р. і «Школа кінорежисури» 1932 р. В багатьох інтерв’ю для газет розповідав про ідею кінокону-петлі – Шлегель.

13 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 47.

14 Олександр Довженко: між тоталітаризмом і національною ідеєю. енциклопедичний словник. т. 1 : а–л / [голов. ред. Г. Скрипник; відп. ред. С. Тримбач]; Інститут мистецтвознавства, фольклористики та етнології ім. М. Т. Рильського НАН України. Київ, 2023. С. 10.

15 Шлегель Г. Й. Олександр Довженко в Берліні // «КіноТеатр» – 2001.- № 2.- C. 46-48.

16 Sutton-Mattocks J. (). Cycles of conflict and suffering: Aleksandr Dovzhenko’s Arsenal, and the influence of Käthe Kollwitz and Willy Jaeckel // Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema. – 2016. – №10(1). – С. 15–46. – https://doi.org/10.1080/17503132.2016.1144279

1 thought on “Довженко в Берліні. Частина І. «Берлінець» Довженко”