Film Information

The film Ukrainian Revolution is a documentary adaptation of the memoirs of Vsevolod Petriv, the major-general of the Ukrainian People's Republic.

He was born in Kyiv into the family of a general of the Russian tsarist army. He graduated from the Kyiv Cadet Corps (1900), the Pavlovsk Higher Military School in St. Petersburg (1902), and the Mykolaiv Academy of the General Staff (1910). In March 1917, he was promoted to the rank of colonel. During the First World War, he was awarded the St. George's Weapon (January 24, 1917 for the battle of May 27, 1915) and all orders up to St. Vladimir III class with swords and bandages for his military services.

Vsevolod Petriv's memoirs tell about his participation in the First Liberation War of 1917-1921.

These memoirs are very important because their author does not describe the actions of the state leaders, but shares his impressions of everything he heard and saw at that time. Thanks to this, a majestic picture of our people's struggle for freedom opens up before us.

The story that Petriv reveals breaks down the myths that there were no patriots in Ukraine, that Ukrainians did not want independence. The depth of patriotic feelings of Ukrainians at that time was no less, and perhaps even greater, than today.

One example is enough: a Ukrainian regiment, self-formed by Ukrainians of the 7th Turkestan (Russian) Division in autumn 1917, was named after Kost Hordiienko, the Otaman of the Zaporizhian Sich, who once supported Hetman Mazepa in his struggle against Peter the Great. Thus, despite Ukrainian history being banned in the Russian Empire, Ukrainians knew their heroes.

The film consists of two episodes. The first describes events from early 1917 until the arrival of the Kost Hordiienko Regiment in Ukraine. The second depicts the events of January–February 1918 in Kyiv.

Premiere of the first episode: 5:00 PM, September 8, 2012, Kyiv, House of Cinema.

Premiere of the second episode: 7:00 PM, May 14, 2015, Kyiv, House of Cinema.

Characters of the film "Ukrainian Revolution"

The main characters of the film are Vsevolod Petriv, commander of the Kost Hordiienko Regiment; Sotnyk (Captain) Andrienko , his deputy; Symon Petliura.

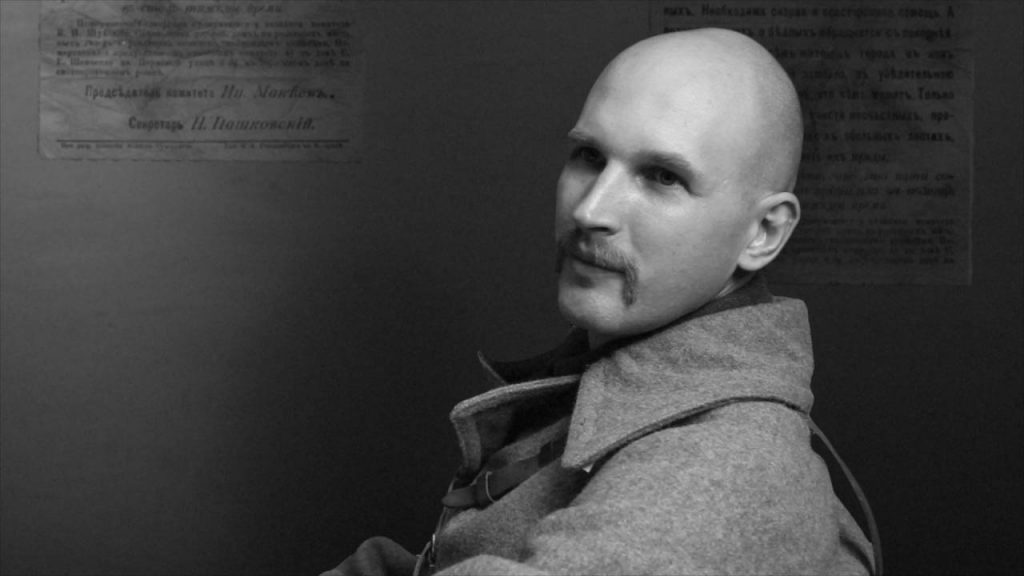

Vsevolod Petriv (Bohdan Ivanko)

Vsevolod Petriv, a colonel of the Tsarist Army, originally from Kyiv region, was the chief of staff of the 7th Turkestan Division during World War I. Later, he headed the Ukrainian regiment named after the Cossack Otaman Kostyantyn Hordiienko, held various positions under Hetman Skoropadskyi, headed the Zhytomyr Youth School, the Northern Division, the Volyn Group, the Military Ministry, and was Chief of the General Staff. Vsevolod Petriv had to witness many political intrigues, collect information about them, but beware of active participation in them.

The 7th Turkestan Division, whose chief of staff Petriv was during World War I, was stationed in the most remote forested area known as the “Nalibok Forest,” covering about a thousand square kilometers between the Neman and Berezina rivers. Notably, amidst the prevailing arrogance and conceit of the officers, Petriv maintained good relations with the ordinary soldiers. After the revolution began, the soldiers sometimes turned to him for advice, seeing him as one of their own.

Perhaps for this reason, Vsevolod Petriv was elected to the divisional committee of the Turkestan Division and, as he himself writes, “took his duties seriously, without joining any of the officers’ factions, and remained on the committee until the separation of the Ukrainians from the 3rd Siberian Corps.” Forced to participate in the activities of committees as well as in corps and army congresses, Petriv became well acquainted with the attitudes of the new military authorities, who considered themselves representatives of the “Soviet of Soldiers' and Workers' Deputies” (original spelling by Petriv).

He took an active part in forming a separate Ukrainian regiment, which was met with strong opposition from the leadership both of the Provisional Government and the revolution. Here is what the author himself wrote about this: “At a time of general disintegration, only the Ukrainians formed an exception; they had no divisions then that were destroying the Russian army; they still represented a unified national collective; their officers looked with disgust upon any ‘officers’ unions’ and worked solely within their Ukrainian circles alongside their rank-and-file soldiers. Only this national unity was seen by some as Bolshevism, by others as counter-revolution.”

Nevertheless, Vsevolod Petriv actively asserted his national stance. He resigned from the position of division commander, explaining that “as a citizen of Ukraine, I cannot, without the consent of the legitimate Ukrainian government, assume command in the Russian army, and therefore I renounce not only the post of division commander but also the position of chief of staff, which I have held until now.”After this high-profile declaration, Petriv worked in the Ukrainian council, the division headquarters as a technical worker, and the corps committee, where qualified personnel were lacking. Forced by these circumstances to travel extensively along the front, Petriv became a vital link between all Ukrainian units, whose leadership was cut off from access to information.

Due to the lack of qualified personnel among the revolutionary military leadership, Vsevolod Petriv had to take part in peace negotiations with the German side as an expert (technical advisor) for the delegation of the Committee of the 7th Turkestan Division. By the way, the presence of a Ukrainian among the General Staff sincerely surprised the Germans, whose leadership mostly considered the Ukrainian idea to be a fiction.

After the situation on the front became critical for Ukrainian units, Vsevolod Petriv, together with the newly formed Kost Hordiienko Regiment, fought their way into Ukraine, where he took an active part in suppressing the Arsenal Uprising in Kyiv. In fact, Petriv’s regiment was one of the few well-organized and trained Ukrainian units on which the Central Rada could rely. Although Vsevolod Petriv did not always support the actions of the Ukrainian Government himself, he was one of those who, through personal observations and conversations with villagers and ordinary soldiers, understood the situation in Ukraine very well.

The author describes it this way in his memoirs: “It was hard to imagine what could be done with such a passive and downtrodden people in terms of rebuilding their statehood. The absence of a sense of national unity and common interests was so great at that time that one felt despair. What kept us going was only an intuitive faith, felt in the villages, in our Ukrainian authorities, an intuitive sympathy for our troops—who spoke in a simple, ‘peasant’ way—that we found everywhere during our difficult journeys through ‘our, yet not our land.’”

The villages near Kyiv, with which I had many connections at the time—because, as a supporter of a territorial militia system even before the war, I used the Tsarist government’s permission to recruit 25% territorial new conscripts to try at least a partial socialization of the army. Thus, commanding a company (by rank as a General Staff officer) in Kyiv, I established close ties with the relatives of my territorial soldiers to make the army less alien and hostile to them.”

With the regiment reinforced in Kyiv after the alliance with Germany—which, by the way, not all of his soldiers understood or supported—Vsevolod Petriv and the mounted Kost Hordiienko Regiment marched across Ukraine fighting the Bolsheviks. Interestingly, under Petriv’s skillful leadership, despite constant battles, the regiment’s strength only grew. Already from Khorol, the unit set out on campaign, “gleaming with brand-new weapons, proudly mounted on fine horses, wearing new splendid hats, now a fully equipped unit of four hundred men with artillery, machine guns, wagons, and communication equipment, followed by two light and three cargo motor vehicles, including Peugeot models with tall wheels capable of easily overcoming poor road obstacles.”

With his regiment, Petriv reached the Crimea and even concluded an agreement with the Crimean Tatar republican government, which he reported to the Ukrainian leadership. But the latter, unfortunately, failed to orient itself in time and use the regiment's achievements. After the defeat of the UNR army, Vsevolod Petriv was interned in Poland.

Victoria Skuba based on materials by Vsevolod Petriv

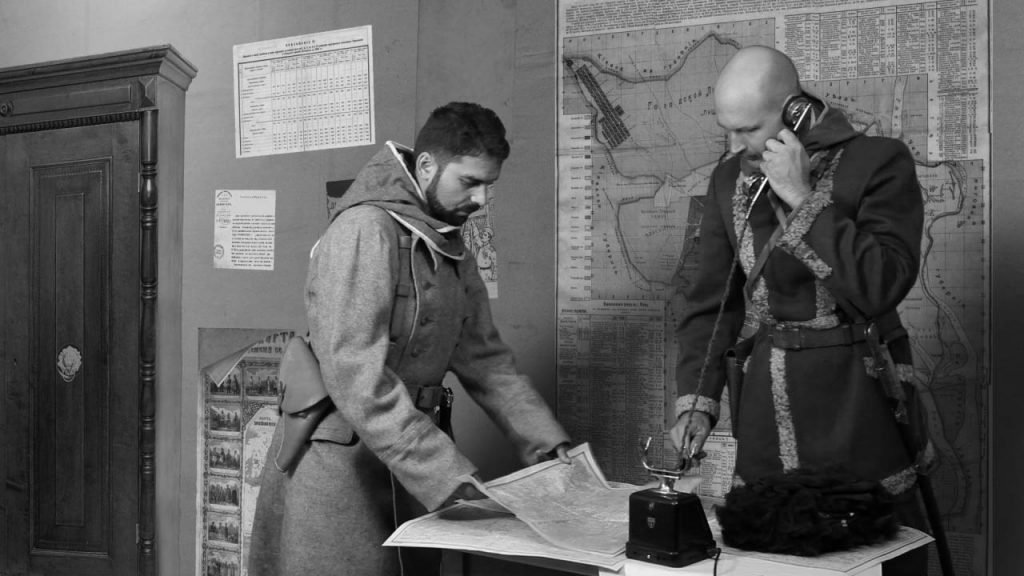

Sotnyk Andrienko (Timur Barotov)

Sotnyk Andrienko was an associate and assistant of Vsevolod Petriv, originally from Poltava region. After the outbreak of revolutionary events at the front, he was elected chairman of the corps council of Ukrainians of the Third Siberian Corps. Together with Vsevolod Petriv, he participated in the creation of the Hordiienko regiment, fought his way through the Belarusian forests to Ukraine, and took part in the suppression of the Arsenal uprising in Kyiv.

Throughout the revolutionary events, he was Petriv's first assistant and made great efforts to protect the Hordiienko regiment from disorganization and theft of property. Later, as the head of the regiment's second company, he fought for Independence against the Russian Bolsheviks and crossed almost all of Ukraine, up to the Crimea. Andrienko's company included those Haidamaks who had formed the regiment at the front. And during the struggle, his combat unit grew to 350 men.

Here’s what Vsevolod Petriv writes about his sotnyk in his memoirs: “Andriyenko was a strange man. A ‘flag bearer’ from among the folk teachers, wounded in both legs during the world war—one leg became slightly shorter because of it, and he limped.

Hot-tempered and unrestrained, he just got into big trouble in Zhytomyr: he met Hrushevsky at the station, approached him and said, ‘What the hell, Father, did you bring the Germans here? This is some kind of nonsense, not politics—it’s a disgrace to the whole world: a socialist negotiating with the Kaiser.’Hearing this conversation, a guard rifleman from the Dnieper region jumped up and rudely shoved Andriyenko, saying, ‘How dare you talk like that to the head of government?’ But Andriyenko replied, ‘He (that is, Hrushevsky) is fortunate that we—the people—elected him, not me, that he is head of government and not me.’”

Andrienko always remained a representative of the left-wing political forces and was the embodiment of the sentiments that prevailed among the ordinary Cossacks. Brave and desperate, he was often exposed to danger and was wounded in battle more than once. He died in 1919 from spotted typhus.

Victoria Skuba based on materials by Vsevolod Petriv

Symon Petliura (Oles Doniy)

In Vsevolod Petriv's memoirs, Symon Petliura, the future otaman of the Ukrainian People's Republic troops and head of the UNR Directorate, appears as an extraordinary and strong-willed, but at the same time controversial and mysterious personality. He is "a short, thin man with a pale, tired face wearing a gray military coat without adverbs and a gray 'soldier's' hat." The author's attitude toward Petliura, a skilled military leader who was respected by his Cossacks, is more positive than neutral, but there is a certain confusion that Petriv feels about the actions of this politician.

Petriv's first meeting with Petliura took place in Kyiv during the Arsenal Uprising as the otaman of the Sloboda Ukraine Kosh. This Kosh was different from other military units based in Kyiv.

“The first meeting with a representative of this Kosh, the head of the patrol, a non-commissioned officer of the Red Haidamaks, left a strange impression on me,” writes Petriv. “Worn-out leather pants, faded from their original red color; a short yellow sheepskin coat; a lambskin hat with a red plume; a shaved head with a long black oseledets (a traditional Cossack forelock) behind the ears; a fresh bullet scar; and an immobile, confidently iron-like face of a maniac—an abnormal man, seemingly a true resurrection of the Haidamak warriors of ancient times…

I asked him: ‘Where is your Kosh?’ A laconic reply: ‘Not far.’ ‘How many men do you have?’ ‘Enough.’ I said: ‘Man, why do you hide it? We are on the same side and must work together.’ He answered: ‘Don’t ask, Colonel! I was ordered to deliver a message—and I delivered it. I have no other orders, so I won’t say anything more. I know where I must return and how the horses will rest; whether you send fresh ones or not—I will return. If you want, write a letter to the Kosh otaman, and I will deliver it, but I cannot tell anyone anything—this is our habit, we Sloboda Haidamaks.’”The Hordiienko soldiers who spoke with the rest of the Haidamak mounted patrol reported that they too said nothing about anything concerning the Kosh. And in appearance, the rest of the Red Haidamaks looked much like this non-commissioned officer.”

But at the same time, Petriv speaks positively about the good military organization of the Red Haidamaks, their excellent intelligence, and a headquarters that is "free of unnecessary people." By the way, it was Petliula's Haidamaks who played a key role in the capture of the Arsenal, which was the main stronghold of those who opposed the Central Rada. But at the same time, it was Petliura who prevented the Cossacks from physically brutalizing the rebellious workers.

Understanding the disorganization within the Central Rada’s headquarters, Petriv did not rule out the possibility of independently subordinating himself to Petliura. However, the latter declined such a proposal: “He gave a very vague answer, saying that he had already taken on too much responsibility and therefore could not interfere with the government’s orders, even though he saw its mistakes. It seemed there were some personal misunderstandings between him and the then government. He only promised to keep in touch with us. I left with nothing, and although I had a good impression of the Slobozhanshchyna people, the vague answer of the Kosh otaman somewhat unsettled me, though it was hard to understand the true reasons behind it.”

Petriv had to face Petliura’s contradictory actions again. After Ukrainian forces withdrew from Kyiv under pressure from Muravyov’s troops, Petriv intended to join Petliura’s Kosh with his regiment, but the otaman “again dodged a clear answer. It was valuable to me only as an experience of how skillfully Petliura maneuvered between the village, his Haidamaks, and some auxiliary detachments, which included, for example, a ‘feeding point’ clearly of a ‘pan-Russian orientation.’

I witnessed firsthand how the village council of Shpytkiv was convinced of the necessity to support their own army, and how it, with a full sense of duty, issued food and forage from a large landlord estate, which had been requisitioned but not plundered by the village; how the head of the village council spoke in a commanding tone to the officers of the Kosh, and the Kosh otaman only nodded in agreement, confirming the need to preserve the people's property. Yet within fifteen minutes, this seemingly gentle man sharply and unfriendly ordered the head of the ‘feeding point’…”

After the Central Rada concluded a treaty with Kaiser Germany, Petliura abdicated his command. It was in his units that the most determined sentiments against the policy of the Ukrainian government of the time prevailed.

Victoria Skuba based on materials by Vsevolod Petriv

When watching from Youtube, you can turn English subtitles on or off.

Watch the film

The first episode of the film "Ukrainian Revolution, memories of Vseolod Petriv" updated in 2015

The second episode of the film "Ukrainian Revolution, memories of Vseolod Petriv"

Film trailer

Film teaser

Downloads of the film "Ukrainian Revolution"

The film “The Ukrainian Revolution”

The first episode in one file.

First episode with english subtitles.

The first episode in one file.

Second episode with english subtitles.

The creative team of the film welcomes its further FREE distribution by all available means.

When posting our movie on other websites, please give a link to ours!

A series of posters "Military units of the Ukrainian War for Independence"

Infographic about the Ukrainian flag of 1917-1921 (in Ukrainian)

Backgrounds for the desktop of the film “Ukrainian Revolution”

Dimensions:

5:4

1280×1024

16:9

1920×1080 | 1366×768 | 1280×720

Dimensions:

5:4

1280×1024

16:9

1920×1080 | 1366×768 | 1280×720

Dimensions:

5:4

1280×1024

16:9

1920×1080 | 1366×768 | 1280×720

Poster for the premiere of the film "Ukrainian Revolution"

The song "The Cossacks rose up" for download in MP3 !

The song "The Cossacks Rise Up", used in the first episode of the movie "Ukrainian Revolution", is now freely available.

It is performed by Taras Kompanichenko and the "Cossack Chorale".

Sound director Andriy Parkhomenko.

The music is folk.

Words by Vira Lebedova (Konstantyna Malytska).