Sergei Parajanov. The Political. When Creativity Becomes a Challenge to the System

The masterful, sensational Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors became Parajanov’s last completed project at the studio named after Oleksandr Dovzhenko, the “father” of poetic cinema in Ukraine. Kyiv Frescoes (of which only screen tests later reworked into a short film survive), Intermezzo, Confession, and The Fountain of Bakhchisarai remained unrealized ideas. Unfortunately, the next Ukrainian stage of Sergei Parajanov’s biography is defined by persecution and imprisonment. How did it happen that a filmmaker-aesthetician came to be perceived as a threat to the Soviet political system?

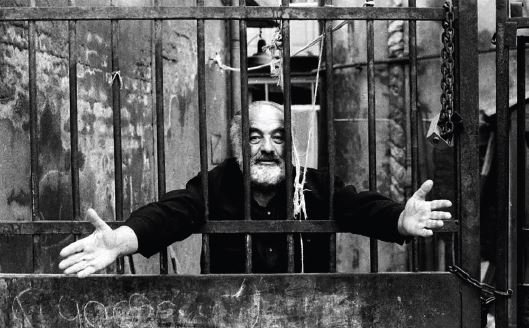

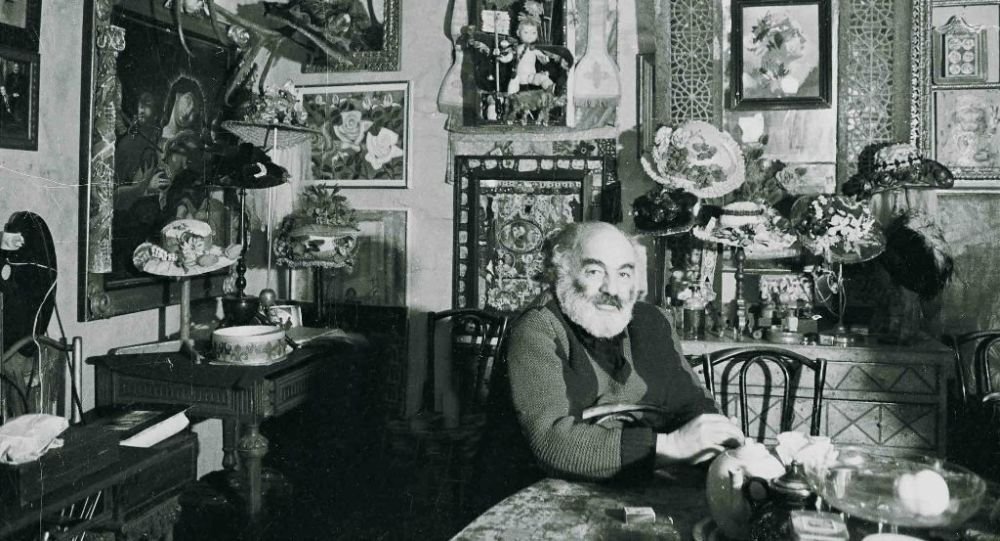

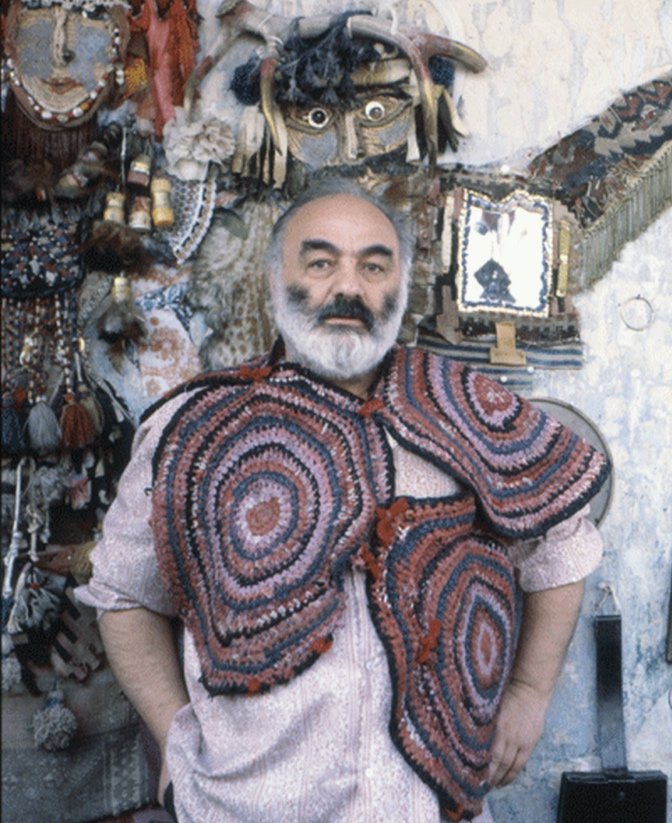

At this point, it is worth speaking about Parajanov’s personality. “Creative” not in the sense that he was an artist, but in the sense that for Parajanov life itself was a creative act. Stories about the director’s artistic nature—about how he could transform reality into a happening—are an indispensable part of the “Parajanov myth,” without which it is impossible to understand his art. Perhaps the most defining aspect of this myth was his gift for transforming space, turning it into a space of art. At the same time, the director’s unconventional thinking manifested itself in the most unexpected creative decisions. Film historian Herbert Marshall described his impressions of visiting Parajanov’s Kyiv apartment: “As you approached, the source of his visual talent became clear: there was not a single painting, sculpture, photograph, or antique object that had not somehow been transformed by Parajanov’s imagination. No work existed on its own, as it had been created. It became part of an overall artistic montage. Each work fused with another, unexpected work: a photograph became a photomontage, a painting—a collage, a classical sculpture—a modern caricature, an icon merged with a modern bas-relief. And this imagination of Parajanov’s revealed itself in his movements and in his conversation.”1Olha Petrova described Parajanov as a representative of the “Baroque person,” “filled with energy, restlessness, and contradictions.”2And the Baroque fit very poorly into the canon-based, rigidly regulated “classicist” socialism with all its regimentation.

Researchers also offer other interesting perspectives on Parajanov’s figure. For example, Lea Feldman examines him through an anti-colonial lens, seeing in Parajanov a representative of the Soviet “southern periphery,” which included, along with Georgia and Armenia, Ukraine as well. What is important in this observation is that Parajanov, through his artistic reflection of this conditional periphery, undermined the declared homogeneity of the Soviet—essentially imperial—space. Parajanov’s orientalism works in the same way—another crucial component of his creativity. To cultural “otherness” he added sexual otherness as well.3

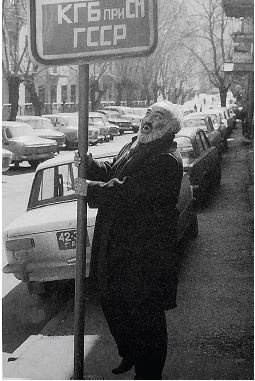

Parajanov was inclined toward flamboyance, and this flamboyance often took risky forms. His disdain for the formalism that so marked Soviet life found expression in the “interior” of the toilet in his famous house in Tbilisi (or “Tiflis,” as he called it in Armenian). Memories of this “interior” survive—an ironic tableau of the director’s past against the backdrop of the Stalin era:“Pinned to the walls were all his documents—his school certificate, his VGIK diploma, a certificate that he had studied a year at the Institute of Railway Transport, a certificate that he had studied two years at the Tbilisi Conservatory in the vocal department, musical awards, honorary certificates for military-patronage activity—and from all the sheets Lenin and Stalin looked at us, and sometimes only Lenin. He would try to accompany his guests to the toilet personally. On a small stand sat a large porcelain vase filled with water, completely glazed and decorated with portraits of Stalin and Mao Zedong with the inscription: ‘Moscow–Beijing–Friendship.’”4In this list, mockery of the almost ritualistic Soviet reverence for documents turns into criticism of the personality cult—but expressed artistically and with humor. Such borderline jokes were not uncommon for him—one need only recall the photo where the director jokingly grabbed the sign near the KGB building in Tbilisi. A characteristic anecdote also survives from Parajanov’s Ukrainian period: once, a huge portrait-banner of Brezhnev was placed across the entire façade of the building where his Kyiv apartment was located. The artist cut out one of Brezhnev’s eyes and waved to demonstrators through the hole. The demonstrators responded with enthusiasm to this flamboyant performance—the “living” eye of Brezhnev—while to the KGB workers Parajanov explained: “I am mocking no one—I’m simply watching the parade of workers through Leonid Ilyich Brezhnev’s eye.”5There are countless such anecdotes about Parajanov; today it is hard to tell what is true and what is legend—especially since the artist himself delighted in cultivating myths about himself—but that is not so important. What matters is that all these stories became an integral part of the Parajanov myth, born of his personality, and to a large extent through their prism he was perceived—by friends, admirers, and... by the security services. An artistic, internally free person fell out of the Soviet way of thinking and living simply by existing—and by existing, provoked others to “fall out” as well.

In a 1988 interview with Ron Holloway, the director described himself as a surrealist who saw a chimera in the social structure: “As if I were a chimera atop Notre Dame, with a huge muzzle and massive hooves, looking down at the city of Paris. I was such a chimera, peering out and envying the coming of a new day.”6In a 1988 interview with Ron Holloway, the director described himself as a surrealist who saw a chimera in the social structure:“As if I were a chimera atop Notre Dame, with a huge muzzle and massive hooves, looking down at the city of Paris. I was such a chimera, peering out and envying the coming of a new day.”Ultimately, this very chimera was destined to play its role in the struggle against the “courtly” aesthetic system of socialist realism.

Thus, Parajanov’s figure did not fit into Soviet reality on any level: through his artistic independence and boldness, through his self-perception as an Author. As Leonid Aleksiichuk aptly put it, he—like a handful of other directors—challenged the system simply by not allowing it into his artistic universe.7He did not fit into Soviet life by his lifestyle either, where among the most egregious “crimes” in the eyes of the system were his flamboyant way of living, his love for antiques, and—what was a separate crime reflected in his court verdict—his trade in them. Finally, Parajanov constantly allowed himself to troll Soviet “reality” and was known for scandalous statements. One such statement to a Western journalist compiling a directory of Soviet filmmakers was that he was anything but a Soviet filmmaker.8

Finally, let us recall the direct political dimension—the “spirit of the time”—in which Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors, and later other films by Sergei Parajanov, became aesthetic projectiles aimed at socialist realism—and at Soviet worldview more generally.

n an interview with Ron Holloway, the director recalled how Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors was received in official circles:“When the officials saw the film, they realized it violated the principles of socialist realism and all that social rubbish that dominated our cinema at the time. But they could do nothing, because it was too late: in two days Kotsiubynskyi’s anniversary was coming—his centenary. And they said: ‘Let him go and show his film.’ The film was released. Later they could have banned it. And then they would somehow have finished the matter. But when the intelligentsia saw it, they were moved. The film triggered a chain reaction of unrest…”9.

The Ukrainian premiere of Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors on 4 September 1965 at the Ukraina cinema also became a political event. Ivan Dziuba walked onstage to present flowers to the film’s artist Lidiia Baikova—and instead addressed the audience, protesting against the arrests of Ukrainian cultural figures. Vasyl Stus and Viacheslav Chornovil supported him, calling on those present to stand in protest. And some spectators indeed began to rise…Of course, the film Shadows of Forgotten Ancestors—an aesthetic manifesto of Ukrainian cinema and Ukrainian (particularly Western Ukrainian) culture—found itself at the center of this story not by accident. The events at the Ukraina cinema revealed not only the protest potential of Ukrainian civil society but also the subversive nature of art that stepped outside the socialist-realist canon. In Parajanov’s creativity, as in his very stance as an artist “above the system,” the authorities saw a threat.

Even the atmosphere of freedom and rebelliousness that formed around the director had protest potential: his Kyiv apartment became a place where one could speak freely and sharply about the authorities.10Finally, he himself showed certain human-rights activism—for example, in 1966 he signed a letter in defense of members of the Ukrainian intelligentsia convicted for anti-Soviet activity (which, of course, the KGB immediately recorded).

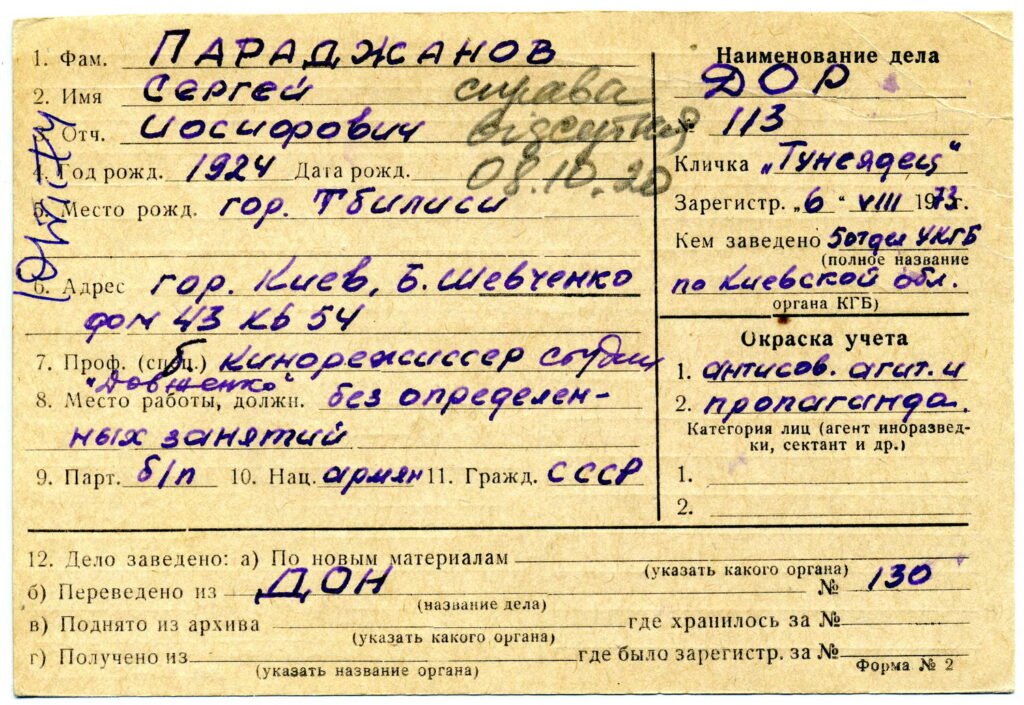

The KGB began paying attention to the director. In a report compiled on him, alongside listing his “attacks against the authorities,” particularly in conversations with foreigners, there is another moment especially important for us:“PARADZHANOV maintains connections with nationally-inclined elements, particularly with DZIUBA, KOLODNY, and others, who are trying to use him in their plans to popularize nationalist ideas in the cinema.”Perhaps the most telling thing about how the authorities viewed his personality is the conclusion:“Many studio employees describe him as a morally degenerate person who has turned his apartment into a gathering place for various dubious individuals who engage in drinking, debauchery, speculation, and politically harmful, and at times anti-Soviet, conversations.”11.

Parajanov was imprisoned three times. The first time—as a student in 1948—he was charged with homosexuality, which in the USSR was a criminal offense. He was sentenced to five years but, as a VGIK student, was released after three months under an amnesty. The second time—already for political reasons. At least, the political basis of the case was obvious, although the formal pretext was again a criminal charge. In 1973 he was arrested again for homosexuality; the indictment also included accusations of “speculation” (he made his living partly by reselling antiques) and “Ukrainian nationalism.” As a result, he was sentenced to five years in a strict-regime labor camp. He served his sentence in the Lukianivka prison and later in a camp in Perevalsk. This imprisonment drew the most public attention: the fate of a world-famous filmmaker did not leave the international community indifferent, and thanks to petitions by cultural and public figures (including writers Louis Aragon and Elsa Triolet, and Lilya Brik, who was very fond of Parajanov), he was released early in 1978. The third imprisonment came in 1982, on charges of bribery—though again, no one doubted the political basis of the case.

Perhaps Ivan Dziuba wrote most accurately about the reasons for Parajanov’s persecution. This long quotation is worth citing in full to summarize and conclude our material:“Did they destroy Parajanov intentionally? There is no direct evidence of this. But this is the essence of his tragedy. The essence lies in the fact that a system built on unfreedom and uniformity, on contempt for the human being, a system of total suppression of the human spirit, operated automatically, ‘like a wound-up mechanism.’ It left no room for creative spontaneity. But when someone refused to bow to the decreed general level, it began to work in a targeted way. Those whose duty it was to maintain loyalist mediocrity—or who built their careers on it—hated Sergei Parajanov: for his talent, for his freedom-loving spirit, for the fact that his films broke through the walls of the aesthetic prison of socialist realism and created a completely different art, a completely different world than the one with which they tried to hold on to one-sixth of the Earth; and for his daring conversations and mercilessly truthful judgments, and for the fact that creative people loved him, gravitated toward him, gathered around him.”12.

1 Herbert Marshall. THE CASE OF SERGO PARADJANOV. Sight & Sound

2 Петрова О. М. Сергій Параджанов як “граюча людина” в контексті мистецтва трансавангарду / О. М. Петрова // Наукові записки НаУКМА. – 1999. – Т. 9, ч. 1 : Спеціальний випуск. – С. 209-211.

3 Leah Feldman. Strange Love: Parajanov and the Affects of Late Soviet (Inter)nationalisms. The Global South, Volume 13, Number 2, Fall 2019, pp. 73-103.

4 Геворкянц Р. Параджанов. Коллаж на двоих. Ереван, 2013, 27. Цит. за: Т. С. Симян. Сергей Параджанов как текст: человек, габитус, интерьер у ΠΡΑΞΗMΑ Journal of Visual Semiotics, January 2019. С. 211.

5 Геронян A. Сергей Параджанов – города в судьбе гения // Вне строк, 24.06.2018. [Электронный ресурс]. Режим до-

ступаhttps://vstrokax.net/istoriya/sergey-Parajanov-goroda-v-sudbe-geniya/ (дата обращения 13.07.2019). Цит. за: Т. С. Симян. Сергей Параджанов как текст: человек, габитус, интерьер. С. 212.

6 Sergei Parajanov Speaks Up. By Ron Holloway. Spring 1996 Issue of KINEMA. Р. 4.

7 Leonid Alekseychuk. A Warrior in the Field. Sight and Sound INTERNATIONAL FILM QUARTERLY WINTER 1990/91 VOLUME 60 No 1. Р. 24.

8 Leonid Alekseychuk. A Warrior in the Field. Sight and Sound INTERNATIONAL FILM QUARTERLY WINTER 1990/91 VOLUME 60 No 1. Р. 24.

9 Там само.

10 І. Дзюба. Він ще повернеться в Україну // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 14.

11 Дзюба Іван, Дзюба Марта. Сергій Параджанов. Більший за легенду – К.: АУХ І ЛІТЕРА, 2021. С. 109-110.

12 І. Дзюба. Він ще повернеться в Україну // СЕРГІЙ ПАРАДЖАНОВ. ЗЛЕТ, ТРАГЕДІЯ, ВІЧНІСТЬ. Київ, «Спалах» ЛТД, 1994. С. 12-13.