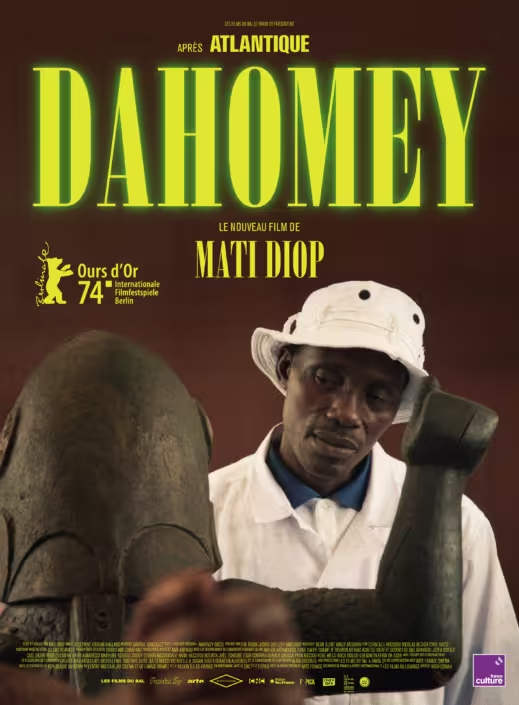

Dahomey... A country that you can no longer find on the political map of the world but one that lives on in history (complex and ambiguous, as it was one of the centers of the slave trade in its time!). And, of course, it lives in the memory of descendants who are now citizens of countries with entirely different names. The film "Dahomey" by French director Mati Diop is dedicated to this memory and its return. This year's laureate of the Berlinale (where Africa, as a whole, became one of the main themes of the festival) explores this topic using a sensitive and painful lens—the story of Africa's colonial conquest and the plundering of its cultural treasures by Europeans.

"Dahomey" (France, Senegal, Benin) begins on a seemingly positive note, with a story of a small victory: the return to Benin from France of 26 historical and artistic artifacts—sculptures depicting local rulers. This restitution became the first of its kind. As Mati Diop, a Frenchwoman of Senegalese descent, explained, the news of France returning African artifacts struck her so deeply that she felt compelled to make a film about it. The preparation of the “26” for their return from a French museum to their homeland and the ceremonial arrival—this is the seemingly simple plot of the film. Yet it raises profoundly complex issues that, if examined more deeply, go far beyond just Franco-Beninese or even European-African relations.

What is the past? How does it affect the present? Can the crimes of the past still shape the fate of new generations, impacting not only collective memory but even identity itself? These are questions that Ukrainians and any other nation that has experienced colonization might well ask. But now—about the former Dahomey.

The film can be roughly divided into two parts. The focal point of the first part is the “26” themselves (as they are self-identified)—the images of rulers, and more broadly, the cultural heritage of former Dahomey that was once plundered and is now seeking its way home. This section is deliberately non-dynamic, with extended shots of packing, flights, unpacking, and preparations for the ceremonial handover. Off-screen voices of the “26” reflect on what they’ve been through and on what awaits them now. An interesting point that Mati Diop touches upon is the chasm that separates the “26” (and, in a broader sense, pre-colonial Dahomey) from the current generation. The collective protagonist is concerned: what awaits them back home, given that so much time has passed? And, actually, do they even have a home there anymore?

An inverse discussion is held in the second part of the film, centered on speeches by young Beninese students and educators—a new educated generation that must come to terms not only with the relatively distant colonial past but also with the more recent postcolonial past and present. It wasn’t just material treasures that were plundered, but also their memory, their past, even their “soul,” they say. The returned “26” provide a reason to talk not only about restitution and about the 7,000 Dahomeyan cultural artifacts that remain overseas but also to discuss education and a sense of identity. “Why did I grow up on Disney, ‘Avatar,’ and ‘Tom and Jerry’ rather than an animated story of Béhanzin [the famous Dahomey king]?” asks one of the participants in the discussion. And, to be fair, this question is directed not at overseas Europe but at Benin's own government. These are new challenges, a different level of responsibility—one that this young generation will soon have to accept.

Is “Dahomey,” with its story of a few returned and countless unreturned treasures, relevant to us? Undoubtedly. In essence, we face these same challenges. The issue of the colonial past, the reevaluation of our own historical heritage and its return, questions of collective memory, even of identity itself—all of this is on the agenda, especially in the midst of an intense phase of war, gaining even more existential weight. Let’s also remember the issue of restitution: how many Ukrainian artifacts are in the museums of our former colonizers, primarily Russia? The number reaches into the thousands. We hope that this question will one day arise not just as a theoretical one but as a practical one. Artifacts from Ukrainian lands will eventually journey back home, allowing us to rediscover ourselves in the process. In the meantime, let’s study Benin’s experience... And let’s preserve what we still have, from old icons to historic buildings—because all of this tells us who we once were and helps us better understand who we have become.